|

| The Tecumseh buoy is off Fort Morgan; Dauphin Island is in background (Civil War Picket photo) |

We added a dollop of Civil War adventure one day, as my wife and I stopped

by Fort Morgan on the west end of the peninsula before taking a ferry across

Mobile Bay to a reenactment at Fort Gaines -- another Confederate fort -- on

Dauphin Island.

From the Fort Morgan State Historic Site parking lot, we walked toward

the narrow beach that on Aug. 5, 1864, was right in the middle of the Battle of

Mobile Bay. Rebel guns thundered at a Union flotilla just a few hundred yards

away. Adm. David Farragut was intent on disabling or sinking the CSS Tennessee

and other ships, taking control of the bay and bringing an end to blockade

running to and from the port.

|

| USS Tecumseh hits a mine and sinks; Rebel ships are to the left (Library of Congress) |

We passed a family that was fishing and eventually saw a multicolored

buoy about 300 hundred yards offshore, between channel markers. Mobile Bay’s

signature oil platforms and Dauphin Island were in the distance.

Is that the spot where 93 Tecumseh sailors and their commander perished

when the ironclad monitor had the misfortune to hit a Confederate mine and sink

within minutes, perhaps even 30 seconds?

There’s no sign or marker on the beach, but when I zoomed in with my

iPhone camera, I saw a large white “T.”

|

| USS Tecumseh model and Confederate mine replica at Fort Morgan museum (Picket photos) |

I will be thinking Monday of the sacrifice of these men and the valor of the sailors on both sides who clashed near Fort Morgan 160 years ago on that day.

Although the state park has a few relics and a model of the USS Tecumseh

in its visitor center, and a sign atop a west-facing parapet mentioning its

loss, I wondered whether many folks know the story of the brave crew

that led the Union charge.

Americans certainly are familiar with Farragut’s line, “Damn the

torpedoes, full speed ahead.”

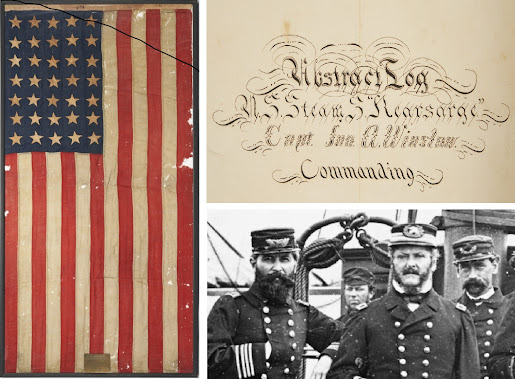

Less known and among Civil War historians and enthusiasts are the reported last words of Tecumseh Commander Tunis Craven (left, photo Library of Congress) moments before the monitor slipped beneath the waves (more on that later in the blog).

This week, I came across an Emerging Civil War blog post that summarized

my thinking better than any words I can conjure.

Editor-in-chief Chris Mackowski wrote about the loneliness and constancy of the buoy, which is maintained by the U.S. Navy as a war grave. The site is protected by the Coast Guard.

He mentioned what a colleague wrote: There are no memorials at sea to

Civil War sailors who died in combat.

“The buoy

used to be farther offshore, but the shore itself has crept closer during the

past 159 years,” Mackowski wrote in August 2023. “How can someone lost at sea ever get back to land when the

land itself keeps moving?

“That lonely offshore buoy serves as a kind of exception to (the) rule.

Something does mark the graves of those men lost at sea. But unless you know

what that buoy is, you don’t know it’s a grave marker, a monument, a memorial.

Thirty feet below, ninety-four men lay entombed in a capsized iron hulk.”

Why the Navy decided to sail into Mobile Bay

I asked Andy Hall, A Civil War naval expert and author, for his thoughts

on the battle and the USS Tecumseh, which he says is shown on modern charts as

an unnamed wreck.

“Mobile

Bay is an interesting action, and it doesn't get as much notice as it warrants.

(None of the naval stuff does.),” he replied in an email. “Mobile was the last

port of significance in the Gulf of Mexico that was supplying the Confederates

in the Western Theater. Galveston (Texas) remained accessible through the

end of the war, but it was honestly too far removed to be of great consequence

in the conduct of the war itself.”

|

| American Battlefield Trust map provides overview of campaign |

“He

is something of a heel among the Confeds for surrendering, but it you read the

detailed accounts he really had little choice, with disaffected and near-mutinous

troops,” said Hall. “Anderson surrendered his sword to Farragut, who later had

it returned to Anderson in respect for his defense of Gaines.”

Hall

said the fall of the bay marked a jump in large-scale blockade running in

Galveston, which is his focus.

|

| We attended an April battle reenactment at Fort Gaines (Picket photo) |

After

the fall of Fort Gaines, Yankee troops moved on Fort Morgan across the bay,

forcing its surrender on Aug. 23, 1864. (The state park had a 160th anniversary

living history on Saturday, Aug. 3.)

Mobile

was heavily fortified and the Union command moved on after securing the bay.

The city surrendered in April 1865, three days after Appomattox.

Ironclad braved minefield to protect wooden ship

In

its rather brief life, the Tecumseh first experienced Confederate mines and

obstructions during operations in the James River in Virginia. Thomas E. Nank,

in two articles for the American Battlefield Trust, provides copious details on

the “Forgotten Monitor.”

|

| The Union Navy was intent on neutralizing CSS Tennessee, shown after the war. (U.S. Navy) |

Between 16 and 18 Federal ships, in two lines, would storm past Fort Morgan, trying to get under the guns, enter the bay and take the fight to opposing ships. Craven, who had expressed some doubts about the effectiveness of monitors but agreed to serve, was first in line on Aug. 5.

The commander, as he

entered a mine field, decided to make a turn so he could

take on the CSS Tennessee and protect USS Brooklyn, a wooden vessel that had faltered amid gunfire from Fort Morgan and the Confederate ships nearby.

|

| Sign on Fort Morgan parapet describes battle, loss of Tecumseh; buoy is beyond (Susan C. Gast) |

Gunners

mate Samuel Shinn, one of about 20 survivors, wrote, “It seemed as if we were lifted right out of the water. At the same time,

a blinding flash like lightning came through the porthole. A large hole was

stove in the vessel's side, and the men below commenced to cry that the vessel

was sinking.”

'After you, pilot.' Chivalry amid disaster

Almost all men below deck on Tecumseh were doomed, but Craven and a few others who were in the turret, pilot house or

elsewhere topside had a chance.

|

| Alfred R. Waud's account of Craven's heroics (Library of Congress) |

Craven and civilian harbor pilot

John Collins, in the conning tower or pilot house, stepped toward a ladder that

would take them to safety. “After you pilot,” said Craven, who never made it

out an drowned in the maelstrom.

Collins, quoted in the

1888 “Battles and Leaders of the Civil War,” said after he spoken with the

skipper, “When I

reached the upmost round of the ladder, the vessel seemed to drop under me.”

In another telling of the story, Coddington wrote, Craven yelled to Collins, “You first, sir.”

An 1879

account of the encounter offers another version of events. It appeared in “A

Sketch of the Battle of Mobile Bay” by William F. Hutchinson, assistant surgeon

of the sloop Lackawanna.

“Captain

Craven was already partly out, when the pilot grasped him by the leg, and cried

‘Let me get out first, Captain for God’s sake; I have five little children!’

The Captain drew back, saying ‘Go on, sir,’ gave him his place, and went down

with the ship while the pilot was saved.”

Farragut's sailors regrouped and won the day

After the Tecumseh

sank, amid "immense bubbles of steam, as large as cauldrons," Farragut realized his mix of wooden and iron vessels, now in disorder, had to plow ahead.

|

| William H. Overend's 1883 painting of the USS Hartford at Mobile Bay (Wikipedia) |

The Federal fleet went on to victory, capturing the Tennessee, while other Rebel ships slipped away, were captured or sank. Admiral Franklin Buchanan, commander of the Confederate fleet, was on the Tennessee and was gravely wounded and captured. (The conquest of Mobile Bay also gave a huge boost to President Abraham Lincoln's re-election bid.)

In a brief

congratulatory order issued the next day, Farragut paid tribute to Craven, paymaster

George Work and their crewmates, Military Images detailed in December 2014.

“It has never been his good fortune,” Farragut stated in the third person, “to see men do their duty with more courage and cheerfulness, for although they knew that the enemy was prepared with all devilish means for our destruction, and though they witnessed the almost instantaneous annihilation of our gallant companions in the Tecumseh by a torpedo, and the slaughter of their friends, messmates, and gunmates on our decks, still there were no evidences of hesitation in following their commander in chief through the line of torpedoes and obstructions.”

Gunner Charles Baker, serving on the USS Metacomet, helped save 10 Tecumseh crewmembers while under fire and later received the Medal of Honor (photo above, U.S. Navy)

Protection and dignity for a war grave

After the war, Tecumseh families railed against granted salvage rights, and the wreck was left undisturbed for a century. Heather Tassin, site manager at Fort Morgan, says the site is believed to be the largest maritime war grave in the continental United States.

A Smithsonian

Institution expedition in the 1960s rediscovered the wreck, and surveys were

later conducted, including one in 2018. There was talk of raising the Tecumseh, but it never happened. The Naval History and Heritage Command

has about 65 artifacts from the wreck, according to an article. Items include ceramics, ship fittings

and hull and deck plank samples.

The NHCC said a management plan continues protection and preservation of the site.

"It is a common misconception that anyone can dive on the Tecumseh," Tassin told the Picket in an email. "No one is permitted to dive on the Tecumseh. It is respected and protected as a war grave."

|

| (Atlas of the Official Records, Plate LXIII, map 6) |

Any proposed research would require a permit

from the Alabama Historical Commission and the Navy. “There would have to be a

very compelling reason to conduct said research because of the Tecumseh’s

status as a war grave and the fact that it has been investigated in an archaeological

study in the past,” said Tassin.

In his

Emerging Civil War article, Mackowski wrote about memorials to the USS Arizona

(Hawaii), USS Indianapolis (Indiana) and USS Monitor (Virginia) – places where

people can walk to, unlike the Tecumseh.

“But in those moments I stood at the mouth of Mobile Bay off the shore

of Fort Morgan, I heard that lone buoy speak volumes. It reminded me of all the

stories lost at sea, untold, unremembered. There are no monuments on the ocean.”