|

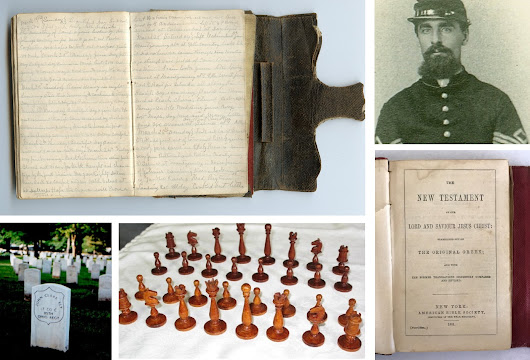

| (Clockwise from top left: Pages from journal, Sgt. John Clark Ely, his Bible, chess set pieces, and his grave in Memphis. (Photos courtesy of John M. Ely, David C. Ely and Jerry O. Potter) |

Beyond

stories about Ely, there are tangible reminders of his life.

John

M. Ely of the Aspen, Colo., area, has his great-great-grandfather’s two chess

sets and a journal (below) that survived the sinking of the steamboat on April 27, 1865,

above Memphis, claiming 1,200 lives. The journal is believed to be the only one

describing the days leading up to the tragedy.

John M. Ely’s second cousin, David Clark Ely of Placerville, Calif., has a Bible bestowed upon his ancestor before he went off to war.

The two men and David’s sister, Sharon Ely Pearson, are open to the idea of the

heirlooms being available to the public through an exhibit or the like.

“I wish we had those items for the museum,” says Sultana

expert and author Jerry O. Potter.

By museum, Potter means the Sultana Disaster Museum across from Memphis in Marion, Ark. Supporters are raising the last of the dollars and pledges needed to build a larger and permanent venue at an old high school gymnasium.

Marion was the closest

town to the disaster and residents helped rescue those thrown into the river

after the fire and explosion on the Sultana.

|

| The tiny current museum in Marion, Ark. A new location is in the works. |

While

the journal has been excerpted in some form for years, the whereabouts of the

Bible weren’t known to Potter and Gene Salecker, another renowned Sultana

author.

“I have never heard of the Ely Bible,

so this is something new to me,” Salecker, author of “Destruction of the Steamboat Sultana,” told the Picket in an email.

I made the story of the

Bible known to the museum supporters after contacting David C. Ely, who I spoke

to several years ago, and John M. Ely, who I tracked down a couple months back.

The Picket has written numerous articles about the Sultana and Ely, and I

wanted to update readers on all the items known to be associated with him.

(David C. Ely and John M. Ely have not been in touch with each other or the Marion museum.)

Sgt. Ely, 37, of Company C, 115th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, was jammed on the overcrowded steamboat with hundreds of other recently released Union prisoners. (He is at left in the photo, next to Company C comrade Sgt. Charles W. Way, who also died on the Sultana.

The Ohio schoolteacher, who was supposed to get a promotion to lieutenant at the end of the war, had been captured by Confederate forces under Nathan Bedford Forrest on Dec. 5, 1864, near LaVergne, Tenn.

Ely (pronounced ee-lee) spent

time in a few prisons, most notably Andersonville, before he was paroled at

war’s end near Vicksburg, Ms.

“He is my hero,” Potter, author of “The Sultana Tragedy: America’s Greatest Maritime Disaster,” told the Picket in April. “I guess I know more

about Lt. Ely than just about any other soldier on the Sultana. In reading his

diary, I was able to see things through his eyes and to learn of his hopes and

dreams.”

Several years ago, Potter told the Picket: “While we have many accounts written later, his is the only

one that we have that gives a day-to-day account leading up to the disaster.

Plus, he is one of the few buried at the (Memphis) national cemetery with a

headstone with his name. Finally, he became my hero who through his own words I

got to know him.”

In his journal (the only one

of two belonging him to survive), Ely writes about his service, family, capture and time in

prison.

On Dec. 25, 1864, Ely wrote, “Such a day for us prisoners. Hungry, dirty, sleepy and lousy. Will

another Christmas find us again among friends and loved ones?”

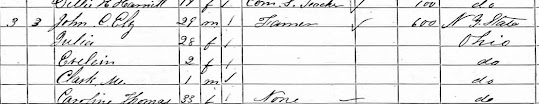

The soldier, born in Franklinville, N.Y., moved with his family as a child to the Cleveland area. The 1850 census shows Seth and Laura Ely and their children living in Cuyahoga County. John Clark was 21.

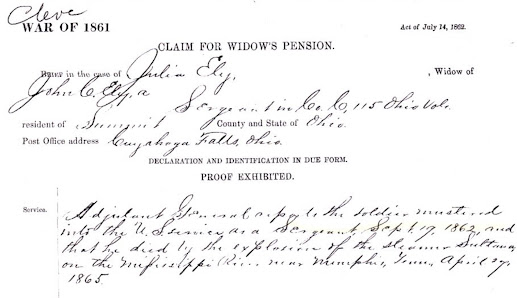

Ely married Julia Richmond (right) in 1856; after his death, she received a pension and moved to Norwalk, Ct., where she died at age 42 in August 1873.

Sharon Pearson told me in 2015 that Julia moved to Norwalk to be closer to her husband’s family and she is buried in Union Cemetery.

“She

lived in Danbury, CT, with several of the other female members of the family

who were widowed or ‘spinsters.’"

The journal, chess pieces and Bible eventually went to the fathers of the cousins. John M.

Ely’s father, Norman, had the journal and chess sets, while the small

Bible went to Norman’s cousin, Clifford Seth Ely Jr., father of David and

Sharon.

|

| Julia Richmond Ely's application for a Federal pension (click to enlarge) |

Norman Ely's mother had told him about the small

diary, which captures the soldier's despair, anguish, privations -- and hope.

(Norman Ely, of Glenwood Springs, Colo., died in March 2013.)

Clifford Ely, a businessman in Norwalk, told the Picket in 2012 he was

touched by his ancestor's time at Andersonville. "There was a lot of

sickness around. Other people stole things from him. It was just a sad thing,

day by day. People tried to escape, (but) he never did."

"He had all the great hopes. He couldn't wait to get home," said Clifford Ely. "When he got on the steamboat, he kept writing to her

(Julia)." (Clifford died in October 2013.)

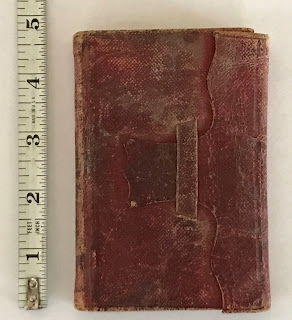

David Clark Ely, 64, and retired

from the U.S. Coast Guard, says he wonders how the Bible survived.

“Did he leave

this behind with his wife or did he take it into the Army? Did he carry it with

him? At one point, it was it separated from him.”

|

| New Testament given to John C. Ely in summer 1862 (David C. Ely) |

Another line appeared to

David and I to read the volume was from “the Church at Stone.” The last word

was hard to decipher so I started checking around the internet. My query on a

Facebook page for Andersonville descendants led me to learn it was “Stow” in

Ohio, where the Elys were living.

The city of Stow has a page about its history, saying eight soldiers from the area were onboard the Sultana and four perished. The Picket reached out to a local historical society for more information but received no reply.

John M. Ely (left), the county attorney in Pitkin County, Colo., confesses he did not pay much attention to John Clark Ely’s story while growing up. “Why did I not listen?”

He saw the chess sets as a child and as he got older he

began to express interest in filling in the gaps of what he knew.

Ely wonders why the soldier and others like him would

leave spouses and children to go to combat. “To me it is a continual fascination and wonderment about

this guy. What was he thinking?”

The attorney has visited Julia’s grave in Connecticut and

a few years after his father passed, he and his children stopped by Memphis to

see John Clark Ely’s grave.

Like David Ely, John M. Ely isn’t certain how the

items survived being thrown into the river. It’s possible, with the exception

of the journal, they were kept at the sergeant’s home in Stow. As for the

diary, perhaps it was found among the debris in the Mississippi or its banks.

John M. Ely told the Picket he never played with the

chess sets. “It seems

fragile and I have never messed with them.”

He is mulling what will become of them and the journal.

If he does

not give them to his children, Ely says he would be interested in an organization,

foundation or museum having them so that they could care for the heirlooms and exhibit

them.

His cousins have not discussed donating the Bible (right), but after talking with the Picket, David says they might be interested in seeing it exhibited as part of a larger narrative.

“There

is a story with it,” he says.

Time will tell whether the items will one day be displayed

in Marion, telling one part of the Sultana’s compelling story.

No one was formally held accountable for putting too many men on the steamboat,

despite documented concerns about the safety of

one of the boat's boilers. Accounts of the tragedy were overshadowed by

headlines about the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.

Potter and Salecker have written about a kickback scheme between the

vessel's financially strapped captain and an Army quartermaster, Lt. Col. Reuben B. Hatch. According to Potter, the

transport fee was $5 for an enlisted man, $10 for an officer. Capt. J. Cass

Mason agreed to take the enlisted men for $3; Hatch kept the $2.

But John Clark Ely knew nothing about that.

Three days before he died, their great-great grandfather

was looking forward to being home. He wrote of a sunny day and boarding the

Sultana in Vicksburg.

Mere hours before the explosion, John Clark Ely wrote

simply: “Very fine day,

still upward we go.”

|

| Additional pages from the Sgt. Ely's journal (Courtesy of John M. Ely) |

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment