|

| A.J. Riddle took photo of prisoners in August 1864 (Library of Congress) |

Like other diarists at Andersonville prison, Pvt. Samuel Melvin faithfully recorded the day’s meager food rations and the weather. These Union soldiers understood the term “death by inches” – the body’s slow descent from illness, exposure to the elements and malnutrition.

Melvin’s little-known

account of his imprisonment at Camp Sumter in central Georgia takes the reader

beyond the grit, grime and the gnawing hunger. His is a journey to the soul.

From daily

entries during the summer of 1864:

June

4: “… It is sad to see

them carry the dead by into the dead house, a continual train of them all the

time. How I hope that I shall live through it and be permitted to enjoy the

true fruition of my life, which I have put so much confidence in and placed

such bright anticipations upon! Still, if I die here I am sure that we shall

die in a good cause, although in a brutal way.”

June 25: “… Sam is in poor spirits, but I am getting as well as could be expected.

But then, I am almost distracted, for things are dubious here indeed, and all

we have to console us is to hope for better things. The seeming joy is great,

that I have in thinking of the joy that I will have when I see the Stars &

Stripes, for then I soon will see my friends. Orders came to give back the

money taken from old prisoners. That is [a] good indication, but money nor

anything can ever compensate us for one week's stop here.”

July 7: “… I

dreamed last night of being paroled and seeing Dow, and the disappointment when

I awoke & found myself still in Hell! — I have given up all hopes of hearing

from home, likewise of their hearing from me. But while there is life there is

hope, and that consoles me.”

|

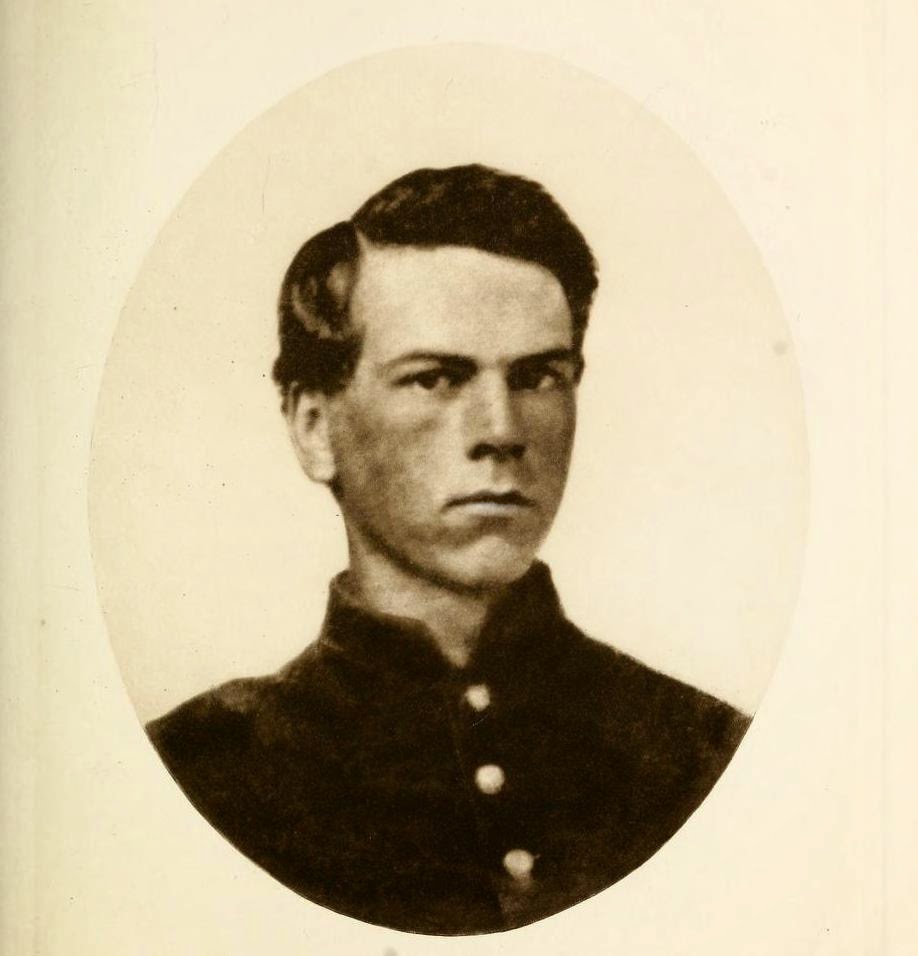

| Samuel Melvin |

Because of

their detail and emotional nature, the words written 150 years ago by Melvin, one of

three brothers to serve in the Civil War, are being featured each day this summer

on Andersonville National Historic Site’s Facebook page. Officials hope virtual visitors will see the prison in a new light.

“Diaries tend

to be very cursory, the variables that change, weather and food,” said Eric

Leonard, acting superintendent. “They don’t often describe emotion or landscape,

but once or twice. Samuel’s diary is very expressive.”

Melvin, of

the 1st Massachusetts Heavy Artillery, and 32,000 others were at

Andersonville in August 1864, the darkest month and the apex of misery at the Confederate

prison.

This weekend’s

“First Saturday” program at the park

will focus on prisoner desperation. Rangers and volunteers will spotlight the

trials of those arriving at Camp Sumter and will take visitors on walks through

the prison site and Andersonville National Cemetery, resting place for nearly

13,000 who succumbed in just 14 months at the prison.

“Relief came

in only two ways that month; a storm that washed over the prison site and

revealed a spring that prisoners called "providential" and rumors of

liberation under General Sherman approach gave hope to the desperate men,” the

park said in a press release. “While the spring water aided the prisoners,

freedom was not so easily gained.”

|

| Re-enactors portray prisoners (ANHS) |

Camp Sumter’s

population had skyrocketed because of Grant’s Overland Campaign in Virginia.

Thousands of Union soldiers taken captive were quickly sent to Camp Sumter.

“By August,

10 percent of the Army of the Potomac is at Andersonville,” said Leonard.

Melvin, 20, was

captured at Spotsylvania, Va., on May 19 and arrived at Andersonville on June

3.

More than

4,000 men had died at Camp Sumter by late July. The situation worsened in

August, when the population reached an all-time high, before dropping

substantially when Atlanta fell in early September and more than half of its prisoners

were moved.

On Aug. 15, 120

men died. Aug. 22 saw 122 deaths and 127 succumbed the next day. There were

many days that witnessed between 90 and 120 deaths.

|

| Captive Thomas O'Dea years later sketched prison, including great storm |

“Shelter is

such a rare commodity,” said Leonard. “All that is being compounded by the fact

you cannot escape the sun and heat.”

Some

prisoners dig into the mud to escape the sun. Others dig in a desperate effort

to escape.

Guards by

late summer have detected 80 such attempts. While 45,000 prisoners were housed

at Andersonville over its existence, only 33 successfully escaped.

“Andersonville

is essentially escape-proof,” said Leonard. “And yet people are trying every day.

A tunnel gives you hope, leadership, coordination and secrecy. Equally

important, it is resistance.”

When caught,

those few who made it outside might be put in stocks or wear a ball and chain

before being thrown back in the general population. “There is nothing worse

than that.”

|

| Plaque shows prisoners using pole, sticks to reach spring water |

There was no

shortage of rumor and speculation among the prison population. Within a few

days, Melvin learned that Atlanta had fallen. Many soldiers were kept alive by

(dashed) hopes that they might be paroled or exchanged.

“The communication

chains are very fast,” Leonard told the Picket. “Getting news …. Prisoners are

hungry for that information.”

Prisoners were

enduring a hot and wet summer. The only place that grass grew through the mud

was between the stockade wall and the dead line, which prisoners could not

cross without risk of being shot.

“If you are

not washing yourself, you get filthy and that feeds into getting sicker,” said

Leonard.

On Aug. 9, a

huge storm arrives at Andersonville. Stockade Creek overflows. Walls on two

ends are breached and guards fire artillery overhead in their call for general

quarters.

The good news

for the soldiers was that much of the excrement that has piled up over the

months is washed away, at least temporarily.

|

| Veterans visit Providence Spring in 1897 (Georgia Archives) |

|

| Providence Spring area today (ANHS) |

According to

tradition, the prayers of many were answered after lightning struck the

miserable compound.

A spring is exposed on the west side of prison,

not far from the dead line. Prisoners attached metal containers to tent poles

or sticks so that they could reach the water. That scene is depicted in a

bronze tablet on the park’s Pennsylvania memorial.

“At some

point a barrel head is played over the spring outlet and they channel it so you

do not risk the dead line,” said Leonard, adding that there are accounts

indicating 2,000 men at a time might line up to draw water.

“In a place

where clean water is dream, this is clean water coming out of a hillside,” said

Leonard. “It was literally a gift from God.”

No comments:

Post a Comment