|

| Renovation of baseball field (Courtesy of Sacred Heart) |

[Click here for a February 2019 update!]

Perhaps it was dropped by a young Confederate soldier working furiously to reload his rifle as his regiment advanced. Or maybe a shot fired by the opposing 14th Maine or 21st Indiana regiments missed its mark and drilled harmlessly into the soil.

Whatever the

circumstances, the Minié ball rested, was covered by more dirt and -- eventually -- by a baseball field at the northeast corner of what's now Florida Boulevard and North 22nd Street in the Mid City area of Baton Rouge, La.

A 1916

Sanborn insurance map shows the ball field being used by African-American teams.

The Stanocolas, a squad fielded by the Standard Oil Company of Louisiana,

followed in the 1920s. Since the late 1930s, Sacred Heart of Jesus Catholic Church -- which did not exist during the Battle of Baton Rouge in August 1862 –

has owned and used the recreational parcel.

All those

years, the bullet stayed undiscovered -- until last week. Crews renovating the

church parcel spotted the artifact in soil excavated for a new light pole.

“You never

know what you might find,” the church’s Facebook page said.

For church

Deacon David Dawson, the find brought some headlines, and a bit of attention.

“I have

people 80 years old coming up and saying they played baseball on this field,”

he said.

Reading about

this tiny bullet led me to delve deeper into the battle, the neighborhood and

the church that serves a diverse flock.

Counting on an ironclad

Baton Rouge

has always been a river city. The Mississippi, unsurprisingly, played a

dominating role during the Civil War, when the capital had about 5,500

residents.

The much

larger New Orleans fell to Federal forces in late April 1862. Baton Rouge was abandoned

and occupied by Adm. David Farragut a few weeks later. Confederates wanted to

regain control of the city so that they could launch attacks along the Red

River and retake New Orleans.

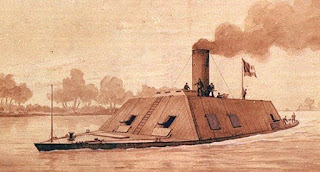

|

| CSS Arkansas (Navy Art Collection) |

Maj. Gen.

John Breckinridge advanced from the east, preparing for the Aug. 5 assault.

Key to success

was the formidable CSS ram Arkansas, which had run through the U.S. Navy fleet

at Vicksburg just a few weeks before. The plan was for the Arkansas to scatter ships

that would drop devastating fire on the attacking Rebels. Parts of the downtown

area were reduced by Federal forces so that the ships could better give support

to artillery and infantry.

William A.

Spedale, in his book “The Battle of Baton Rouge,” wrote: “With the aid of the

Arkansas, the Confederates had every reason to feel confident of victory, and

the Yankees knew it. Their old wooden ships were no match for the low-profile

iron-clad ram.”

Confederates gave it a shot

|

| Click to see battle map |

The

entrenched Union forces had positions at what is now Sacred Heart church and

its ball field. At that time, it was just woods and fields.

Breckinridge’s Hunt and Smith brigades began the push toward the river and the fighting extended to the public cemetery (now

called Magnolia Cemetery, across the street from Sacred Heart and its ballfield).

“A fierce

fight soon developed across the length and width of the cemetery, most of it in

hand-to-hand combat. The tomb and monuments were chipped and pockmarked where

Minie balls struck them, and the magnolia and cedar trees were scarred and twisted

from cannon fire,” Spedale wrote.

The Rebels

pushed the Yankees back toward the river, but had to endure artillery rounds

lobbed by U.S. Navy ships. They knew something was wrong.

A National Park Service summary gives the rest of the story.

“The Arkansas could have

neutralized the Union gunboats, but her engines failed and she did not

participate in the battle. Federal land forces, in the meantime, fell back to a

more defensible line, and the Union commander, Brig. Gen. Thomas Williams, was

killed soon after. The new commander, Col. Thomas W. Cahill, ordered a retreat

to a prepared defensive line nearer the river and within the gunboats’

protection. Rebels assailed the new line, but finally the Federals forced them

to retire. The next day the Arkansas’s engines failed again as she closed on the Union

gunboats; she was blown up and scuttled by her crew. The Confederates failed to

recapture the state capital.”

|

| Damage to Baton Rouge from the battle (Wikipedia) |

Phillip E.

Faller, author of “The Indiana Jackass Regiment in the Civil War," told the

Picket that Federal forces withdrew a couple weeks later.

“They got the

message from Gen. (Benjamin) Butler to burn the town, and get on the transports

and get down to New Orleans.”

Some of the

community was burned. But the Confederate hold of Baton Rouge was short-lived.

It was reoccupied a few months later and was in Union hands for the duration of

the war.

|

| View of national cemetery across street (Sacred Heart) |

Few reminders of the battle

Of course, many

artifacts have turned up in Baton Rouge in the decades since the Civil War.

|

| Bullet marks behind marker (J. Potts) |

“I have heard

of people over the years going into Magnolia Cemetery and finding this and that,”

said Mary Lee Eggart, an artist and archivist for Sacred Heart.

The city

today is known for being the headquarters of state government, a large

petrochemical industry and Louisiana State University.

John Potts,

program director for the Baton Rouge Civil War Round Table, said there are few

Civil War spots to visit today.

One is the national cemetery, below Magnolia

Cemetery. It contains the remains of Union dead. The Foundation for Historical

Louisiana and other groups hold a memorial service at Magnolia Cemetery each

summer.

|

| (Courtesy John Potts) |

“It is now

under concrete,” Faller says of the majority of Civil War Baton Rouge.

But there are

still some reminders of the bloody fighting near and on what is church ground.

Several headstones at Magnolia Cemetery bear fading nicks and damage from

bullets.

Baseball field has seen many teams

Sacred Heart

of Jesus came to the neighborhood in 1924 as a mission of St. Joseph Church. Its picturesque basilica rises above the community and a parochial school is across

the street.

Within

decades of the Civil War, Baton Rouge was growing to the east. The church

served Italian immigrants who came in the late 19th century. The

congregation at that time gathered a block away.

|

| Click to enlarge (Courtesy Sacred Heart) |

The ballfield

was not then in church hands. Early in the 20th century, it was

marked as a “Negro” ball park.

“It is

uncertain exactly when the area became a ball field, but as early as 1916, a

Sanborn insurance map of Baton Rouge notes it on the far eastern edge of the

city as ‘Ball Park,” a church history of the field says. “The 1923 Sanborn

insurance map of Baton Rouge labels it as ‘Base Ball Park,’ and shows

structures labeled ‘grandstand’ and ‘bleachers.’”

The Standard

Oil team, the Stanocolas, and the Cotton States League Highlands played on the

field in the 1920s. “Children would wait for foul balls to sail over the

third-base wall and then stage a bicycle relay through Magnolia Cemetery to

hold on to them. These souvenirs were collected and exchanged for game tickets,”

the history says.

|

| Map shows relation of field to Civil War units (P. Faller/ML Eggart) |

Sacred Heart, wanting to expand, in 1937 purchased the parcel containing the ballfield and what would become the sanctuary. (Improvements to the field were made in the following years.)

“Despite the

hardship of the Depression the parishioners were very generous” and raised

money for the new building, Eggart said. It was completed in 1942.

Peak

membership was in the 1950s, when the church had about 1,200 families. Today,

there are about 800.

|

| 1947 aerial photograph of the church, field below it (Sacred Heart) |

Serving community's many needs

Sacred Heart,

which describes itself as having traditional worship, is a fixture in a

neighborhood with many challenges. The area is largely African-American and there

are many poor families.

“We are on

the edge of North Baton Rouge, which has been for many decades a very

impoverished part of town,” said Eggart, a lifelong church member.

While most

Sacred Heart members live outside its traditional boundaries, about 20-25

percent of members are black. “We are probably one of the more diverse

congregations in Baton Rouge,” said Dawson.

Sacred Heart

has one of the largest Society of Saint Vincent de Paul groups in the parish,

making home visits and helping residents with bills.

|

| (Courtesy of Sacred Heart) |

Collections

from some Masses go to the society, Dawson said. Most who live around the

church are not Catholic, but the church considers itself strong in charitable

giving.

“The biggest

challenge is people coming to church,” he said.

There’s been

a concerted effort to breathe new life into Mid City, through development and

low-cost housing. Part of the effort is spearheaded by the city; and there are

groups, including the nonprofit Mid City Studio, which is fostering entrepreneurship and cultural resources.

Eggart said

revitalization in downtown Baton Rouge in the past decade is starting to spread to Mid City.

“The immediate area

around the Sacred Heart campus has only seen minimum effects as of yet,

possibly because it is more residential and the Mid City growth has largely

been with new businesses locating there. But we are hopeful that the trend will

continue in our direction as Mid City becomes more attractive as a place to do

business AND to live.”

After Easter, it will be 'Play ball!'

Dawson, the

church deacon, was put in charge of the ball field overhaul as a “last hurrah”

before he goes to seminary in New Orleans.

|

| Magnolia Cemetery is on the other side of the fence (Sacred Heart) |

The renovation

includes new metal light poles, large safety nets, grading, leveling and

resodding. The bullet was unearthed when crews dug down about 3 feet for the

light pole. It’s not clear how deep down the artifact had been resting.

Besides baseball, the field is used by church-affiliated groups, including a young girls running group, practice for softball and flag football teams, and child soccer. "We also on occasion let non-school teams use it," said Dawson.

The church is having a family day after Mass on April 8. Gov. John Bel Edwards have been invited to throw the first pitch.

Staff members

are tossing around ideas, but Dawson said perhaps it will be hung on the

concession stand wall, with a placard. “When people come to the games they can

see it was a battlefield. I don’t want to put it in a jar.”