|

| Barnard's fascinating photograph showing Union engineers (Library of Congress) |

I

love his descriptions of Federal soldiers posing for the camera. Among them:

“Blue-eyed

dandy”

“Jaunty caps”

“Photobomber”

“A dude

checking his iPad”

You get the

idea. But an image he posted on January 4 of soldiers destroying Atlanta

railroad in November 1864 especially got my attention. George Barnard, a

contractor for the U.S. Army, took many photographs of the fallen city after he

arrived two months earlier, but I had never seen this one, for some reason. While

most of these fellas were just standing around, others were engaged in a flurry

of activity before the end of occupation and the commencement of the March to

the Sea.

Labeled “Gen. Sherman’s men destroying the Railroad, before the evacuation of Atlanta, Ga.”, the photograph was taken in downtown Atlanta not far from skyscrapers, Underground Atlanta, Mercedes-Benz Stadium and the former CNN Center. (Detail from Georgia Battlefields Association walking tour map below)

It shows two groups of men destroying railroad track and machinery, vital to Confederate transportation in the Deep South. The larger contingent gazes at what appear to be pipes or boilers. The freight depot for the Western & Atlantic Railroad is in the background.

What exactly

is shown here? I decided to reach out to Barnard authority Keith Davis and Atlanta-area experts for their

thoughts: The Atlanta History Center, Civil War author Steve Davis and The Atlanta Campaign History and Discussion Group and Uncle Billy’s Boys (Western Federals), both on Facebook.

Also

consulted was the Georgia Battlefields Association, which will conduct two walking tours of Civil War Downtown Atlanta in March, using Barnard photos as reference

points.

Why

was Barnard in Atlanta in 1864?

Barnard, a pioneer in the field, served as the official photographer of the Military Division of the Mississippi, led by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman. He wasn’t primarily a photojournalist. A number of his works were reproduced in the illustrated papers of the day, and some stereographs were sold to a popular market.

On July 28, 1864, Capt. Orlando Poe, Sherman's talented chief engineer, wired Barnard (right), who was in Tennessee: "Hold yourself in readiness to take the field if telegraphed to that effect." A few days after Atlanta fell, on September 4, Poe telegraphed Barnard to join him, shortly after Hood’s Confederate troops, cut off from supplies, abandoned the city.

The Atlanta of the Civil War was a boom town, just beginning

to acquire the muscle and mettle that one day would make it the behemoth of the

South. In 1860, on the war’s eve, it had fewer than 10,000 residents, making it

the fourth-largest city in Georgia, behind Savannah, Augusta and Columbus.

With its nexus of four railroad lines, Atlanta quickly showed

its importance to the Confederacy and Federal forces who finally reached its

outer fortifications in July 1864. The city quickly descended into chaos as Rebel

troops were moved around and supply lines threatened.

Davis, author of several books on the Atlanta Campaign,

including “What the Yankees Did to Us: Sherman’s Bombardment and

Wrecking of Atlanta,” has written extensively about Barnard’s

documentation of the Union conquest of Atlanta, with scores of scenes showing

destruction, fortifications, a slave mart and Sherman himself.

In the volume “100 Significant Civil War Photographs: Atlanta Campaign,” Davis (left) said Sherman and Poe wanted their troops to destroy only manufacturing and railroading capacity, which was concentrated in the downtown business district. Federal soldiers, Davis wrote, started their own fires as early as Nov. 11, 1864.

“We are fritened (sic) almost to death last night,” young Atlanta diarist Carrie Berry wrote. “Some mean soldiers set several houses on fire in different parts of the town.”

The three photographs I will be discussing here – showing destruction of the city’s railroad infrastructure – were taken by Barnard in mid-November 1864. They likely were taken within a short time of each other, and may include some of the same troops.

What’s

going on in this picture?

It’s hard to

get a consensus because there were few detailed photo captions in those days and it’s

just plain difficult to know for sure, given several pieces of iron or steel

jammed together.

Poe, in his

set of images, wrote of this one: “View in Atlanta just before the ‘March

to the Sea’; showing manner of destroying Railroads and Machines.”

Jackson

McQuigg, vice president of properties for the Atlanta History Center, which

houses the giant Cyclorama painting and Civil War exhibits, said he thinks the largest

item in the foreground is a stationary steam engine (used for power

generation).

“The boiler is at right, while the stack is flopped over and laying on its side on top of the engine itself,” he writes. “Even though the caption said that Sherman’s men are destroying ‘the railroad’ I see rails at left … it sure looks like that’s mostly pipe on the ground in the front. Maybe those were locomotive boiler flues?”

Charlie

Crawford, president emeritus of the Georgia Battlefields Association, theorizes

the foreground may depict a boiler on the right and a detached exhaust chimney

(long tube) lying on a flat car.

“It could be

an exhaust chimney for any piece of machinery that creates heat by using

controlled flame,” he wrote. “The boiler is the item on the right of the flat

car. It still has an end cap, unlike the hollow tube. Could well be that

the exhaust chimney was paired with the boiler before the machinery was

disassembled.”

Commenters on

Adelman’s Facebook added these guesses:

The

‘toolbox’ looks to be a toolbox on top of a steam piston from a locomotive. A

boiler appears to be behind the smokestack and toolbox.....and there appears to

be steam pipe fittings on the platform as well.....possibly a disassembled

locomotive.

What it is resting on to the right of the picture appears to be a steam engine cylinder and valve box.

As for the rest of the photo -- the men toward the back?

Michael Rose, curator of decorative arts and special

collections at the Atlanta History Center, said the smoke emanating from the

back half of the photo (above) are three fire pits built to heat the rails. The idea

was to warp and bend the rails and render them useless.

“I suspect the men are waiting for the

heat to do its job so they can do theirs before moving on to more,” Adelman wrote

in his Facebook post.

Later in this post, I examine two more destruction photos.

What exactly is that writing on the iron?

Zoom in on the flat car or platform and you will see a

horizontal piece of iron with writing. It’s tough to make out (and for me to brighten) but here are some posts from commenters on the Adelman Facebook post.

"Laimbeer & Co. Atlantic Dock, Brooklyn, NY, 1855" which was one of the main warehouse companies located at Atlantic Dock.

“ATLANTIC

DOCK BROOKLN NY 1855”

Rose said he can make out Brooklyn, N.Y.

“But not what

comes before it, undoubtedly the manufacturer’s name. It does look like it

includes “Atlantic” – but not in a way that look like Western & Atlantic

R.R.”

Who are these soldiers?

According to Steve Davis, Sherman initially assigned three

regiments of the provost guard to oversee the destruction: The 111th

Pennsylvania, 2nd Massachusetts and the 33rd

Massachusetts.

Their task to destroy track, the roundhouse, depots, the

railroad car shed and more, said Gordon Jones, senior military historian and curator at the Atlanta History Center.

The general changed his mind and brought in professionals -- Poe’s 1st Michigan Engineers and Mechanics and the 1st Missouri Engineers – to carry out the work. The 58th Indiana also pitched in, according to Crawford.

Poe (right), chief engineer of the Military Division of the

Mississippi, supervised demolition of the main passenger depot in downtown

Atlanta and many other buildings. He is remembered as a visionary engineer, for

both military and civilian service.

In his memoirs, Sherman wrote of “Poe’s special

task of destruction.”

Not only did Poe carry out the order to burn

Atlanta in 1864, he built the roads and bridges that made Sherman’s March to

the Sea possible, according to the National Park Service. “At the end of the

war, he was named brevet brigadier general. Since no system of medals existed

at the time, the brevet rank, meaningless in terms of real authority, served to

recognize gallant conduct or other meritorious service.”

Where

was the photograph taken?

Downtown

Atlanta was an extremely busy hub for railroads serving the city and much of

the South. The photograph was taken fairly close to the juncture of the Western &

Atlantic and Macon & Western railroads.

|

| GBA map of downtown; W&A depot is shown at far left (Click to enlarge) |

“In the background

is the W&A RR depot,” says Crawford. "Depot site would now be just west of

Ted Turner Drive and just northeast of “The Gulch.” Photo was taken from

WNW of the depot, about where CNN Center used to be.”

The W&A roundhouse would be to the left, outside the image, said Rose.

The Barnard photo below -- taken before its destruction by Yankee troops -- shows a different angle of the depot, this time with a large roundhouse in the background. The facility was used for servicing locomotives. (Photo: Library of Congress)

|

“As Yankee

engineers proceed with their destructive work, smoke drifts past the ruins of a

destroyed building in this original Anthony stereo view. Indeed, there was

plenty to dread as night fell on Nov. 15, wrote John Kelley and Bob Zeller. “It

was, (Maj. Henry) Hitchcock wrote, “the grandest and most awful scene.”

When

was the photograph taken?

Regarding the

shot of the men standing around the metal pieces, Steve Davis believes it was taken

around Nov. 10-11, days before much of the city was torched.

Keith Davis (left), a leading expert on Barnard, told the Picket the photos of soldiers destroying railroad were likely taken on both Nov. 14 and 15. Sherman’s troops began leaving the city before noon on the 15th to begin the march to Savannah, Ga.

“On the following morning, the general staff, Barnard, and the remainder of the Union

forces marched out of the shattered city,” Davis wrote in a book about Barnard.

“So, I have to think that Barnard was extremely active

on Nov. 15; thus, making

it correct to date these as Nov. 14-15,

rather than strictly the 14th,” he told the Picket.

Crawford doesn’t

believe the photographs could have been taken Nov. 15.

“We can date these photos because they depict activity,

and we know the car shed and rail lines were destroyed on 14 November. Since the armies left town

on 15 November,

the photos must have been taken on the 14th. Barnard may have

taken images as the armies were leaving, but the destruction was completed on

the 14th."

The one major

gap in Barnard’s Atlanta photography is that no images exist showing the vast

panorama of destruction after the fires of Nov. 15 and 16, according Kelley and

Zeller in the “Battlefield Photography” newsletter.

What about the two other soldier photos?

|

| Union engineers destroying track; Western & Atlantic depot behind (Barnard, Library of Congress) |

The first photograph described here was taken very

close to the main image we have been discussing. Barnard must have moved his

camera forward. If you look closely, you can see the men working amid iron

rail, wooden ties and other infrastructure.

The photograph with all the machinery shows a

particularly tall soldier. I am trying to place him in this photo, and I

wonder if he is the man wearing a hat with a round crown, his face not visible to

the camera. But the hats don’t exactly match. I welcome guesses from anyone

reading this. These men are believed to be from the 1st Michigan and

1st Missouri engineers.

The second photograph, a vintage original stereo view, depicts men heating

track near the destroyed car shed, about 700 yards east-southeast from the

machinery shot.

|

| Sherman's men do their work; behind right are remnants of car shed (Barnard, Library of Congress) |

This scene is mostly covered today by the Central Avenue overpass downtown. Smoke from burning railroad ties rises in the background, according to Kelley and Zeller, who date the photograph to Nov. 15. The view is to the west, said Crawford. (Below is a photo of the car shed before its destruction)

“This has

been a dreadful day,” Carrie Berry wrote on Nov. 15. “Things have been burning all

around us. We dread to night because we do not know what moment that they will

burn the last house before they stop.” (Her journal is at the Atlanta History Center)

|

| Modern view (below) is above where car shed was built (Library of Congress and Georgia Battlefields Association) |

“Present day photos are difficult because construction of

the viaduct system in the 1920s put the roads 20 to 30 feet higher than the

terrain shown in the 1864 photos,” said Crawford. “You can still look down from

a few vantage points onto the existing freight line and the two MARTA tracks

that occupy some of the space that the multiple rail lines once traversed.”

You can get an idea of the modern landscape from the photo (above) of Lot R parking area that is above where the car shed was formerly.

Sharing blame for all that destruction

Let’s briefly step back for a little background on what’s been termed in folklore as the Burning of Atlanta. About 40 percent of the city was in ruins when Sherman began his March to the Sea. But don’t lay all the blame solely at his feet.

“It started when Confederate military planners stripped and leveled buildings and homes on the city’s outskirts to build the extensive fortifications that Sherman found impenetrable,” reads an online presentation, “War in Our Backyards,” produced by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and the Atlanta History Center for the 2014 Civil War Atlanta centennial.

|

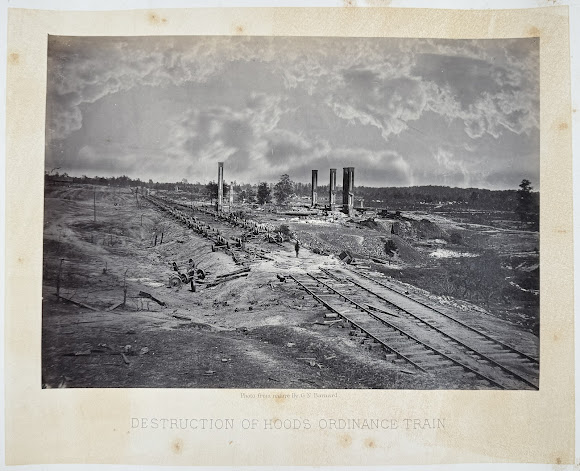

| Hood's troops blew up ammunition train before leaving (Barnard, Fleischer's Auctions) |

Looters, arsonists and the need for material for Union forts took their toll until November 1864, when Sherman “ordered the destruction and burning of all facilities with potential military value, including ripping up rail lines and destroying Atlanta’s transportation infrastructure.” He ordered out the remaining civil population, who were offered a one-way train ride either north or south.

Steve Davis has written about how the fires spread to residences, and some Union soldiers decided to start some residential blazes of their own.

You can see sites in March walking tours

Sadly, virtually nothing from wartime downtown Atlanta

remains today and only a guided tour and some imagination can provide an

adequate picture.

Crawford

has led the GBA walking tour for 18 years. I went on a version in 2014 with

former The Atlanta Journal-Constitution editor Scott Peacocke in July 2014. I

enjoyed it and wrote about the experience here. “It rained buckets,” Crawford reminded me.

|

| Scott Peacocke, Charlie Crawford and Mary-Elizabeth Ellard in 2014 (Picket photo) |

Crawford

works from a downtown then-and-now map and a PowerPoint presentation with

Barnard photos. The slides include pointers and basic information. He then

takes participants around the area to see the “now” view to correspond to the

old images.

“It’s always fun to hear people say that they had seen some of Barnard’s photos and always wondered where they were taken,” he said.

Particularly popular are references to the book and movie “Gone With the Wind", including a scene in which Scarlett O’Hara approaches the car shed, which had been turned into a receiving hospital under care of Dr. Meade.

She walks through the expanse created by multiple rail lines, and hundreds of injured Confederate soldiers, some on stretchers, some on the red soil or tracks, writhe in agony or lie motionless. It is a powerful scene, punctuated by a tattered Rebel battle flag.

Crawford said he gets a variety of reactions and questions during his tours.

“Discovering

that not all of Atlanta was destroyed is difficult for some to accept. Seeing

that the state Capitol is now on the former City Hall site seems to give most

people something they can surprise their family with.”

----

Georgia

Battlefields Association will again lead free Phoenix Flies tours GBA of Civil

War downtown Atlanta. Participants must preregister for the March 8 and 22

walks, which take about 2 hours and 45 minutes. The tours are limited to 25

people. Click here for more information. Registration for Phoenix Flies begins

Feb. 21.

No comments:

Post a Comment