|

| Rebel gun emplacements remain at memorial site (Picket photo) |

The Episcopal clergyman-turned-soldier had kept his headquarters for a few days at the George Hardage home near Kennesaw, Ga.

|

| Hardage home near Kennesaw (Picket photo) |

|

| Capt. Simonson |

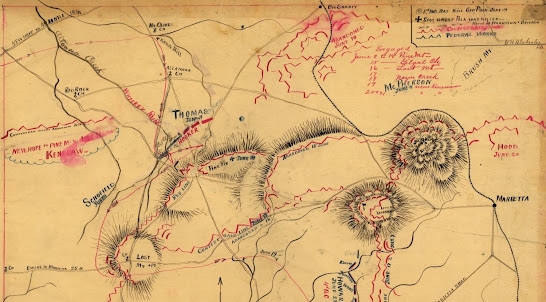

Maj. Gen.

William T. Sherman noticed the Southern generals on the ridge just 600 yards

away. “How saucy they are,” he is reported to have said. The commander ordered

Federal batteries to spring into action.

Simonson’s

battery opened fire and after one shot went over the generals’ heads, a colonel

urged them to move to the rear. Johnston and Hardee moved away, with Polk

trailing.

“Two more

shots came whining down in quick succession. One of these two … struck Polk in

the left arm, ripped through his chest and tore his right arm before exploding

against a tree,” author and historian Russell Bonds wrote in the May 2006

issue of Civil War Times. “He was blown back toward the crest of the hill, and

lay with his feet toward the enemy. ‘General Polk is killed!’ the men in (Capt.

Rene) Beauregard’s gun emplacement cried.”

News of

Polk’s death spread quickly. The Union command intercepted wigwag messages that

asked, “Why don’t you send me an ambulance for General Polk’s body?”

So it was very likely that Simonson knew that his battery could take credit, although others claimed to have fired the lucky shot. But he wouldn’t live to tell the story in old age. On June 16, Simonson, was shot and killed just a few miles away from Pine Mountain.

I recently

visited the death sites for Polk (left) and Simonson in neighborhoods full of Civil

War history. It was here that both sides bobbed and weaved as Sherman relentlessly

marched on Atlanta. He would have a significant setback at Kennesaw Mountain two

weeks after Polk died before his troops won several key battles and took

Atlanta -- a huge blow to the Confederacy.

Polk’s death

site features a fenced memorial erected in 1902. It is near the remnants of

three Confederate gun emplacements and a couple homes. While the mountaintop

had been cleared of trees at the time of the fighting, the neighborhood is now

wooded. The memorial is just a short walk from Beaumont Drive. (Note: Cobb

County roads are largely busy and I suggest special care when stopping to look

at memorials and signs.)

A stone pillar

contains some information about the general, who was extremely popular in the

South but is considered by most historians to be arrogant and a mediocre

general, at best.

|

| Alfred Waud depiction of Polk's death (Library of Congress) |

“Folding

his arms across his breast, He stood gazing on the scenes below, Turning

himself around as if to take a farewell view. Thus standing a cannon shot from

the enemy's guns crashed through his breast, and opened a wide door through

which his spirit took its flight to join his comrades on the other shore.”

Interestingly,

on the reverse are the words, “NORTH. Veni Vidi Vici. With 5 to 1.”

According to

the American Battlefield, Polk was “loved by his

men, due in large part to his geniality, commanding presence, and lax attitude

towards discipline.” He felt comfortable being a warrior and a clergyman

wrapped in one.

While Polk

was a West Point graduate, he had no other military experience before he joined

the Confederate army. In the intervening years, he had been a clergyman in

Tennessee and Louisiana.

An expedition

led by Polk into neutral Kentucky early in the war prompted the state to ask

for Northern aid, a blow to the Confederacy. In 1862 and 1863, Polk led troops

at Shiloh, Perryville, Stones River and Chickamauga. He feuded often with Gen.

Braxton Bragg but had favor with President Jefferson Davis.

Over the years, the Leonidas Polk Memorial Society and Sons of Confederate Veterans have held memorial services at the site. A 2017 article in the Marietta Daily Journal provided details of one such SCV event.

“The blood of

a hero baptized this mountaintop, and the baptism still resonates to this day,”

one attendee said of Polk, wearing his uniform at left.

A post on the society website says Polk was a martyr who fought for liberty and freedom.

The monument does not mention that Polk, born to a wealthy family in North Carolina, owned scores of enslaved persons and was a full supporter of secession.

“Our ancestors fought and died for

something they believed in, and whether we believe in it or not, we want to

honor them, because they are our ancestors,” the lieutenant commander at the

Leonidas Polk SCV Camp told the newspaper. “People just don’t realize what’s

gone on around here and the truth about the war. I think they should come to

these things that we invite everyone to. We don’t care about what race they

are; we don’t condone slavery.”

A few miles from the Polk memorial (detail at right), the spot where Simonson fell is marked by a green marker in front of a home on Frank Kirk Road. The text reads:

CAPTAIN

PETER SIMONSON 5th Indiana Battery

Acting

chief of artillery for the 1st Division (4th Army Corps), Simonson on June 16,

1864 was busy entrenching here a 4-gun battery of artillery when he was killed

by a Confederate bullet. The Confederate was perhaps a sharpshooter armed with

an English made rifle with scope known as a Whitworth. The Whitworth fired a six-sided

bullet that could kill a target one-half mile away. However, the two armies

were within a few hundred feet of each other at this point, so it is not

unreasonable to believe he could have been killed by a common Confederate

rifleman.

Park ranger Lee

White, in a post several years ago for Emerging Civil War, described the

Whitworth.

“Whitworth Rifles were an engineering marvel, hexagonal bore with an

accurate range of over one thousand yards when sporting the 14-inch Davidson

scope along the side of its barrel. In the hands of a trained marksman, these

were a force to be reckoned with.”

|

| (Civil War Picket photo) |

“Simonson, who only two days before had ordered the shot that killed Leonidas Polk, and who had stopped Hood’s flank attack at Resaca, rolled a log along the ground as he crawled on his belly with some infantry skirmishers along a rise several hundred yards in front of the Confederate line,” White wrote for Emerging Civil War.

“All of the sudden, he stopped and lay with his

face to the ground as a crimson patch began to expand from his head. Simonson

had ventured a brief peek above his log at the Confederate line and was

instantly shot through the forehead, depriving the army of one of its most

talented artillerists.”

Simonson’s

loss was lamented in the army. A March 1894 article in the Indianapolis News

about his daughter details some of the captain’s service.

|

| Click to enlarge (Library of Congress) |

Bonds also

shoots down part of a 1932 Sherman biography that claims a battery of Ohioans

commanded by former Prussian artillerist Capt. Hubert Dilger was responsible.

|

| Polk the clergyman |

Today,

Simonson is little remembered. But Polk is, despite his death being considered by many historians as not a great

loss to the Confederacy.

Pvt. Sam

Watkins, who saw the general’s mangled body being carried from Pine Mountain on

a litter, later wrote: “My pen and ability is inadequate to the task of doing

his memory justice. Every private soldier loved him. Second to Stonewall

Jackson, his loss was the greatest the South ever sustained.”