|

| Early model of Montauk; section of blueprints (SCAD) and Professor Johnson describing its operations (Picket photo) |

Carter would

like to see it positioned next to an old model of the CSS Nashville

(Rattlesnake), a commerce raider the Montauk blew out of the water in

February 1863.

Greg Johnson says

completing and printing a precise 3D model of the Montauk -- one of 10

Passaic-class monitors -- will be a boon for graduate student Wilson Han, who

is in his gaming class at the nearby Savannah College of Art and Design.

“A legacy piece,” Johnson says of the effort.

And Han (left), a native of China, is likewise excited by the project, which involves modern technology and a bit of old-fashioned model-making.

“I am always interested in history,” he says.

Now, five years after Johnson visited the park and met

former interpretive ranger Mike Ellis, the dream of having a Montauk model is

finally close to reality. Han has been working on the model design for the past

couple months, using Autodesk Maya software. Han said April 1 the modeling is going well but slowly because of a busy college quarter.

The original goal of the project was to create compelling

interpretive panels, a 3D ship model and film that explained the role of USS

Montauk and other innovative Federal monitors in the siege of Confederate

outposts on the Atlantic Ocean, specifically Fort McAllister.

The plan turned out to be too ambitious, given SCAD graduations

and the complexity of work, which ran up against limited class time. Still, a

half dozen wall panels and a schematic of the Montauk were created by SCAD students and installed in late 2022.

Work on a model stalled after that, but when I reached back

out to Johnson, interactive design and game development professor at SCAD, back

in December, he asked for contact information for park leadership (Ellis had

left by then) and I connected him with Carter.

|

| Jason Carter measures CSS Nashville exhibit to aid in model for Montauk (Picket photo) |

Johnson stressed the work would be tedious, that Han would

have to check all specifications and ensure the model was ready for printing.

“I have to be certain to do the job right,” Han told the

Picket.

Accuracy is paramount, says Johnson, who located the likely

paint scheme for the ironclad

“It will be down to the bolt,” he says of the reproduction.

|

| The Nashville was trapped near this bend in the Ogeechee River (Picket photo) |

Finding blueprints was a stroke of fortune

Ellis, now a guide and trainer for Old Towne Trolley Tours in

Savannah, recalls being in a storage area at Fort McAllister in 2017. There

were piles of documents and papers everywhere.

“As rangers

come and go, things get lost to time,” he says.

Ellis went

through some of them and found a matted long tube. Inside: A precious copy of the

USS Montauk’s blueprints, manufactured in dozens of sheets.

|

| One of numerous photos of blueprints shows turret (Courtesy Greg Johnson) |

Everything clicked during Johnson’s visit to the site. “Me and Greg spent a better part of

the day taking photos of (the blueprints) in detail.”

They used a

custom-built rig to slide dozens of sheets under a camera to obtain high

resolution.

“These images were then processed, enhanced

and stitched together using photo editing tools to make the panels,” Johnson

says. The image could then be used for the wall, model or the film.

Showdown on the Ogeechee was one-sided

|

| USS Montauk receives fire from Fort McAllister as it hammers the Nashville |

The Union navy, as it continued its chokehold on Southern

ports and readied for offensive operations, sent the Montauk and sisters Passaic, Patapsco and Nahant, supported

by gunboats Seneca, Dawn and Wissahickon to bombard and capture Fort McAllister

in January 1863.

The skipper of the Montauk was John Worden (left), famous for being the USS Monitor’s captain when it clashed with the CSS Virginia in 1862.

Capable Confederate gunners at Fort McAllister

hit the ironclad 13 times in its first action, but caused little damage. A

second attack on Feb. 1, 1863, found the vessel, according to histories,

pounded by 48 shells. The Montauk's sister ships also took part in the action.

Its big day came on February 28. The sidewheeler Nashville, which was bottled up and hiding under the guns of Fort McAllister for protection, tried to get away from the Federal ironclads via Seven-Mile Bend on the Ogeechee River, but apparently ran aground.

The 215-foot blockade runner commanded by Lt. Thomas Harrison Baker became a sitting duck because of its lack of maneuverability and deep draft in a

tight area, and the Montauk pounced.

“All the monitors were designed for littoral or riverine operations, and so drew as little water as possible,” says Hall. “Nashville was built as an ocean-going steamship, so had a fuller, deeper hull.” That proved to be a disadvantage at McAllister.

Montauk’s XV- and

11-inch Dahlgrens were able to destroy the former commerce raider.

Worden was pleased with his destruction of ‘this

troublesome pest’” wrote John V. Quarstein, director emeritus of the USS

Monitor Center in a blog.

“However, Montauk suffered

a huge jolt when it struck a Confederate torpedo en route down the Ogeechee

River. Worden’s quick thinking saved his ironclad.” (Quarstein’s new biography of Worden will be published April 15).

The Union naval attacks on Fort McAllister itself were less successful. The low-profile

earthen fort could withstand the shelling and repairs could be readily made.

While the Montauk was scrapped in the early 1900s, the park grounds and museum have a large number of CSS Nashville artifacts.

|

| USS Montauk (left) and USS Lehigh in Philadelphia in 1902 (Wikipedia) |

On the afternoon of my visit, Carter, Johnson and Han -- who is majoring in game development and interactive design --

met in a conference room and a museum gallery that houses the wall panels,

artifacts and the CSS Nashville model.

Carter used a tape measure to get the dimensions of the

Nashville display case. That was to help ensure the Montauk 3D model would be

built in the proper scale (1/78).

|

| Wilson Han and Professor Johnson are working from this paint scheme (Courtesy Steven Lund) |

Carter provided these vital statistics for the two warships:

Montauk, 200 feet long, beam 46 feet, draft 10 feet

Nashville, 215 feet long, beam 34 feet, draft 20 feet

While the monitors were mass-produced, they did undergo

changes during the service, and SCAD students wanted to be sure the appearance

of the Montauk matched the time it prowled off Fort McAllister.

SCAD is working from a Montauk paint scheme described in the

work “Modeling Civil War Ironclad Ships” by Steven Lund and William Hathaway.

The deck is lead gray, the turret and pilot house black with

a narrow white ring, and the smokestack black with the upper one third in dark

green.

To distinguish them, all 10 Passaic ironclads had some color

variations.

Sources for such information on paint schemes are difficult to find, says model maker and writer Devin J. Poore.

“Black is very popular, (while) gray

and white were used in really hot areas.”

3D printing is not for the faint of heart

Converting an item intended for a game to a 3D printable

object requires numerous revisions.

The former are designed with much higher resolution so they

can be used in interactive entertainment. Former SCAD student Collin Drilling

created the original image of the USS Montauk. It had about 10,000 “holes;” he

worked from May and Zbrush software.

Han’s task was to bring down the resolution and fine tune the

details. Johnson had worked on the turret, and his student used that as a

guide.

|

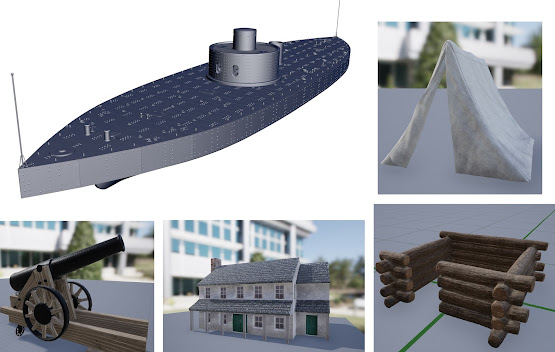

| A version of the Montauk model before Han's work to modify it for printing (Courtesy SCAD) |

The printer is like a dot matrix and the artist must

determine how many pieces he should make for the ironclad model and figure in

joints for assembly. While Han wants to keep it to perhaps one to three pieces,

some items require more, says Johnson.

Poore (photo below) told the Picket the

quality of any model,

handmade or 3D designed and printed, depends on the skill of the modeler.

“3D models come off the printer needing sanding, priming, assembly, etc. Depending on how much work you put into the process depends on the result. There are certain benefits that 3D printing can have over hand making, such as pretty much guaranteed right angles and symmetry, but then again you have to worry about how to actually print a piece so that it comes out cleanly, and so that it won't warp in the future,” he says.

This project is a mix of newer and old technology. While the

printing will produce the frame of the ship, finer pieces such as chains and

rigging will need to come for a model kit or the like.

And the painting is definitely old school; Johnson said he

expects to assist with that.

Passaics were primo, but had limitations

For Fort McAllister, the Montauk model will help further its

education of visitors on the fort and various Federal attempts to subdue it.

Lund said the innovation and quality of the Passaic class

made for the best monitors.

“Although two of the 10 produced were lost, some of them

soldiered on into the 20th century. At least two were recommissioned

to serve as harbor defense vessels in the Spanish-American War. One of them,

the USS Camanche, guarded the San Francisco Bay during that conflict. She was

sold for scrap in 1908 and her hull functioned as a coal barge as late as WW II.”

|

| A model of the U.S.S. Carondelt being made for 3D printing (Courtesy Devin J. Poore) |

“For the work

needed on the Atlantic coast, i.e. reducing forts, they weren't the best

candidates. They were built to fight Confederate ironclads, and simply didn't

see much action in that regard, due to the limited number of Confederate

opponents.”

Poore is in

the process of making his first full-blown printed ironclad, the city-class

U.S.S. Carondelet. The vessel had notable service in the Western Theater.

|

| Devin J. Poore's model of the USS Weehawken (Courtesy of the creator) |