|

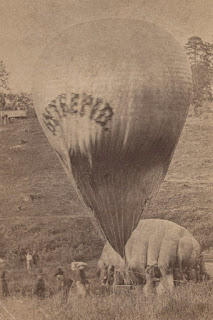

| Union troops inflate Intrepid at Fair Oaks in Virginia (Library of Congress) |

But, unlike

the Chinese suspected spy balloon that was shot down off the coast of South Carolina this weekend by a U.S.

fighter jet, no Union or Confederate airships were lost. They were behind front

lines and too difficult to hit.

The flight of

the unmanned Chinese craft over multiple states was a reminder that spy balloons have

been used since the 19th century, seeing particular service in Lowe’s

Union Army Balloon Corps.

For two years – until the corps was disbanded due to bureaucratic and logistical issues and indifference – Lowe’s brainchild provided valuable, if limited, service in spotting Rebel positions and putting them on the defensive.

|

| Thaddeus Lowe observes Battle of Fair Oaks from the Intrepid (Library of Congress) |

The

Picket reached out to historians and writers who have documented the use of

seven Federal and two Confederate balloons during the Civil War. We asked Knapp,

historian Michael G. Stroud, author Russell K. Dutcher III and Gail Jarrow about their use during the conflict, changes in technology and the role of military balloons today.

Did the use of balloons have a major

impact on the conduct of the Civil War?

Before we

tackle that, a little previous balloon history is in order.

“Most people

may not be aware that the use of balloons was proposed to the

hierarchy of the U.S. Army during the Mexican-American War. Unfortunately, the

use of the balloons was discounted by higher command authority,” says

Dutcher, author of the book “Union Army Balloon Corps.”

“The introduction of military ballooning was proposed during the Seminole War, but again, fell upon the short-sightedness and unwillingness of the U.S. Army to accept new technology,” he said.

While the use

of balloons never really got off the ground for the Confederacy, they did

garner advantages for Federal forces in the first half of the Civl War.

After the

Union disaster at the Battle of Bull Run (Manassas) in July 1861, both sides

regrouped and expanded recruiting. Concerned that Confederates would cross the

Potomac River and take Washington, Federal aeronauts took to the air.

“Balloons went up in multiple locations from Edwards Ferry to Buds Ferry making observations and reporting which helped calm the general public and gave the North a greater chance at regrouping,” says Knapp. (Intrepid at left, Library of Congress photo)

The balloons gave observers a bird’s-eye view of the topography that was previously unheard of or unthinkable, according to Stroud. Two of the more well-known Federal craft were the Intrepid and Union. The small Confederate fleet included the Gazelle.

In and around the capital over the coming months, engineer Brig. Gen.

John Gross Barnard designed and built 68 forts, a task made much more urgent by the ignominious Union defeat Manassas.

Rebel troops weren’t far from the capital – in Falls Church, Va. The Union Army Balloon Corps spied on them from Fort Corcoran.

In Virginia, along the Potomac River, among the most imposing Confederate

defenses was Cockpit Point Battery in Prince William County. Perched atop a

70-foot bluff, the fort had an air of mystery from the beginning. It was built

in secret, with trees left in front to better hide the construction. Curious

Federal troops on the Maryland side of the river eventually used a balloon to

try to figure out how many men were at Cockpit Point and other batteries in the

area.

At

Island No. 10 in the Mississippi River, John Steiner’s Eagle balloon surveilled

Rebel strength and defenses. Steiner directed Federal fire from 500 feet up,

tethered to a ship. The island was eventually taken.

|

| Balloon Intrepid watches fighting at Fair Oaks in May 1862 (Library of Congress) |

Outside

Richmond when Union forces were separated in two by a flooded Chickahominy

River, multiple ascents and reports by Lowe helped reunite the forces and saved

hundreds of lives,” says Knapp, who has portrayed Lowe at events and talks.

“Any time the balloons went aloft, the Confederates had to move their positions. They made false camps; matched in circles to kick up dust to give the impression they had more forces on the ground and they made false campfires at night,” he says. “All (of) this distracted and took time away from actual fighting. Look at all of the attention the China balloon (distracted) us from other more important things.”

In

the end, Rebel aeronauts made fewer than 10 ascensions in 1862. Their enemies

made about 3,000 flights from 1861 to 1863.

“I never

understood why the enemy abandoned the use of military balloons,” wrote

Confederate Brig. Gen. and artillerist Edward Porter Alexander. “Even if the

observers never saw anything, they would have been worth all they cost for the

annoyance and delays they caused us in trying to keep our movement out of

sight.”

|

| Kevin Knapp in a reproduction balloon and at site where Thaddeus Lowe landed in South Carolina |

By the Civil War, balloons had moved from construction of linen and paper filled with hot

air to those made of durable varnished silk, powered by hydrogen and helium

gasses.

“Thaddeus Lowe made his a balloon inside of a balloon

knowing they’d be used in a field environment: corn stubble, bush and tree

stumps – anything but a freshly mowed lawn,” says Knapp.

Aeronauts

could reach altitudes between 500 and 3,000 feet. Lowe tethered his balloons to

the ground to provide a stable platform for aerial observation and so

information collected could be delivered to the ground commander immediately, says

Knapp. Observations were made by line of sight, aided by binoculars or

telescope. Wind, trees and obstructions could limit the visibility.

According to Stroud (left), balloons would remain largely unchanged until the 1960s, “when Edward Yost utilized a propane burner to control a balloon’s ascension and descent thus allowing for a degree of balloon control that had not before existed.” Balloons now could carry their own fuel.

Today’s balloons have a thick vinyl envelope, and the helium or hydrogen allows significant lifts that are limited only by the size of the envelope.

Lifting gas expands with increased altitude, according to Knapp, and observation equipment may include radar, infrared, photo imaging and radio frequency sensing -- "all at the same time, in every direction for miles.”

How has their use in

military/surveillance matters evolved since the 1860s?

The bulky and

cumbersome balloons of the Civil War, with their labor-intensive field hydrogen

gas generators, where outfitted with the highest tech of the day for field

observation and reporting.

“Militarily,

balloons has been used by various world powers since the 1850s predominately as

an observation platform, but there were instances where it was used as a

bombing platform such as the siege of Venice in 1849,” says Stroud. “The U.S.

military considered using balloons as early as the 1830s during the Second

Seminole War and even more so during the Mexican-American War of 1846-1846 to

break strong Mexican defenses, but none were executed.”

|

| Barrage balloons protected against aircraft at Normandy (Wikipedia) |

Military balloons

took major steps forward during World War I, and the conflict also saw the use

of dirigibles, including the Zeppelin raids of Britain.

“WWII would

see the use of barrage balloons or blimps by the UK as part of their defense

network to thwart German bombers and V-1 attacks, the Japanese use fire

balloons with explosives to cause terror to Americans on the West Coast, the

Soviets used them to assist in artillery spotting and the U.S. Navy utilized

balloons in their anti-submarine operations,” says Stroud.

While not

receiving much publicity, balloons continue to be used as strong surveillance

tools and assets by many countries. “The cheap cost structure, when combined

with a balloons ability to stay aloft longer and over targets of interests,

have made it an ideal platform for intelligence and information gathering,”

according to Stroud.

Does this event give you any new

thoughts on the practical role (or limits) of balloons to conduct surveillance?

Even with super sophisticated technology, there is something to be said for simplicity, Stroud says.

“Balloons in the military continue to surprise in their value and role

diversity from nuclear test detection, to observation and most importantly,

intelligence gathering. This alone shows world powers and nations that one does

not have to spend millions if not billions on complex military platforms or spy

satellites when a fraction of the cost can be invested in disposal yet

effective balloons outfitted with surveillance gathering equipment to spy on a geopolitical

adversary.”

They still provide a high rate of return

Stroud says

military balloons provide a high rate of return for the investment.

“We have yet

to develop and implement a relatively cheap surveillance platform that allows

one to rise to 60,000 feet (or higher) and therefore out of the range of most

fighters, keep eyes on a target for longer than satellites can and provide

valuable intelligence on said target like a balloon can,” he says.

Navy Lt. Cmdr. Steven D. Culpepper, writing in 1994, said the usefulness of information gleaned by balloons matured during the Civil War. Logistical problems decreased as aeronauts gained experience.

Knapp, who has participated in balloon races, says colleagues have had “to thread the needle” to avoid going into Chinese airspace. And he recalls when two Americans died when their balloon was shot down over Belarus in 1995.

He criticized

U.S. leaders for waiting for the Chinese balloon to go over the ocean before it

was taken down. Officials had said they were worried about shooting it down over land, were debris could potentially harm people or structures. China has insisted the balloon was used for civilian purposes.

“All

of the information collected was immediately received by China as it was

collected. We should have shot it down as soon as it entered our airspace,

period,” Knapp says.

What would Thaddeus Lowe think of all

this?

The aeronaut

and scientist, as head of the balloon corps, would be impressed with modern

ballooning and electronic technology, according to Knapp.

“Lowe would feel extremely vindicated in the longevity of the balloon as a platform and as

a military asset,” Stroud says. “He argued vehemently as to its value with

President Lincoln and continued to do so up until his dismissal from the Union

and the disbanding of the balloon corps.

“He instinctively and fortuitously saw the need for the military to be able to gain greater situational awareness of its surrounding and to gather data, with balloons being the only way to do that. He was only limited by the resources and primitive technology of the time, but his vision became a reality in both our military and those throughout the world.”

One

interesting side note on Lowe (above) involved his own adventure only weeks before the

Civil War erupted.

Reading about the path of the Chinese balloon reminded her of Thaddeus

Lowe’s flight from Ohio to the Atlantic Ocean (Washington, D.C., area) in April

1861, says Jarrow, author of “Lincoln’s Flying Spies: Thaddeus Lowe and the Civil War Balloon Corps.”

Lowe had future plans to cross the Atlantic in his balloon, and this was

his test flight.

“Unfortunately, he came down in South Carolina eight days after Fort

Sumter. The locals weren’t too pleased when they realized he was a Yankee,”

says Jarrow. “Lowe was arrested, and some wanted to hang him as a spy. No one,

including Lowe, knew that within three months, he would be a Union spy. He was

eventually released and took a train north immediately.”

No comments:

Post a Comment