|

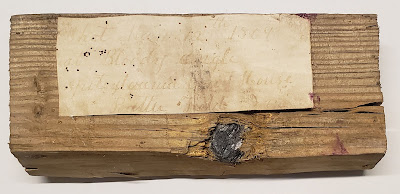

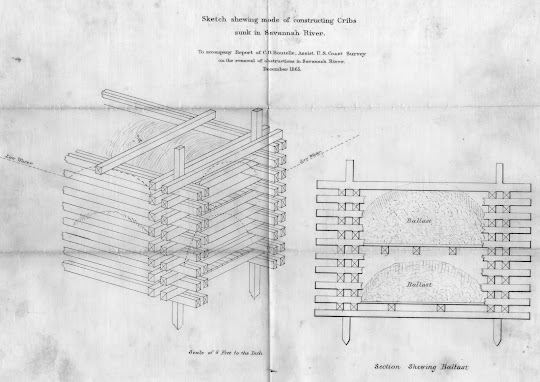

| Design of cribs placed in the Savannah River -- click to enlarge (National Archives) |

Confederate forces towed the wooden obstructions,

believed to be about 40 feet by 40 feet, and put them in place near Fort Jackson and

the ironclad CSS Georgia, a floating battery that was part of the Savannah

River defenses.

“They were severely degraded. They were not in great

shape,” U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Savannah District archaeologist Andrea Farmer

said of the condition of what are termed Crib C and Crib D. But a few portions, including the corner of one crib, had remained mostly intact.

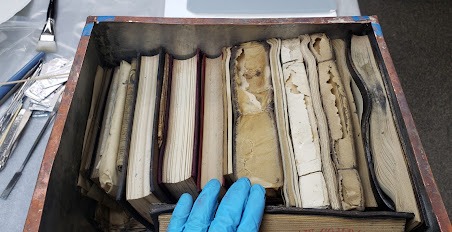

Contract divers using sonar last fall located four of the cribs on the South Carolina side of the river. Cribs A and B were previously explored and the dives in November and December concentrated mostly on C and D, Farmer told the Picket earlier this month.

The Corps is in charge of the ongoing deepening of the

Savannah harbor and the dives are part of an investigation of historical resources

that have been or could be affected. The Corps recently concluded the recovery

of artifacts from the CSS Georgia, which was scuttled by its crew in December

1864 shortly before Federal forces took Savannah and was in the current shipping channel.

While tourists to the popular coastal destination gaze

upon the supertankers coming from or to the Atlantic Ocean, they likely have no

idea what lies beneath the surface: Remnants of vessels, pieces of Native

American pottery that washed down stream, and other items deposited over the

centuries.

|

| View of cribs from multibeam survey. Dredged channel is in blue (USACE) |

The Confederacy used a wide

array of weapons and obstructions to deter advances on Savannah from the sea.

Besides forts and warships, wooden cribs, pile dams, torpedoes (mines), snags,

logs and shipwrecks were employed.

Unlike the cannons, the four cribs will be left in place.

They are not expected to be directly affected by future channel deepening

because they are on the northern edge of the project, Farmer said.

Corps officials referred to period maps and descriptions from Union Corps of Engineers Capt. William Ludlow and Capt. Charles Boutelle for information on the cribs. Boutelle, working for the U.S. Coast Survey, made a December 1865 survey of obstructions in the Savannah River.

|

| Topographic view of four cribs from survey. Dredged channel is in blue (USACE) |

She said the cribs initially would have been at or near

the surface but years of deterioration have reduced them mostly to debris a few

feet about the river bottom.

“Crib

A may be the most well preserved, as it seems to have the greatest amount of

material based on the current height of the obstruction. Cribs C and D contain more material than Crib

B, both in terms of extant structure and rubble/brick fill based on the areas

that have been excavated.”

The Corps said it hopes to

provide photos of the dives soon.

|

| Examination of harbor from the city to Elba Island (USACE) |