A monument near the back of Columbia (Mo.) Cemetery, where black

people were buried when the graveyard was segregated, is the city’s newest

memorial to veterans. It lists the names of 42 men who served in the U.S.

Colored Troops, formed to employ former slaves to defeat the Confederacy. The stone

includes every black soldier whose burial can be verified. • Article

Saturday, August 27, 2016

Friday, August 26, 2016

Restoration and rebirth: Famous locomotive Texas readied for new home in Atlanta

|

| (Max Sigler, preservation specialist, Steam Operations Corp.) |

When

a crane early next year gingerly sets the Texas into place at its new home at

the Atlanta History Center, the legendary locomotive will be on full view to

motorists and pedestrians.

The “showcase” position fronting West Paces Ferry Road will be a

far cry from the Texas’ basement view for 90 years at the old Cyclorama

building 10 miles south in Grant Park.

For

those behind the restoration of the 1856 locomotive – a participant in the “Great

Locomotive Chase” during the Civil War -- it’s a well-deserved honor. When

construction is completed, The Texas will be in a glass-enclosed breezeway

leading to the massive Cyclorama painting, the companion piece that will be

moved from Grant Park and restored.

“The Texas is

Atlanta in one object,” said Jackson McQuigg, vice president of properties at

the AHC. “It is why we are here.”

That’s no

overstatement. Railroads largely are what made Atlanta, which was a vital

junction before and after the Civil War. The Texas was among the workhorses of

the Western & Atlantic Railroad and other companies.

|

| (Max Sigler, preservation specialist, Steam Operations Corp.) |

Since late December 2015, the locomotive and its tender have been receiving a much-needed

restoration in the back shop of the North Carolina Transportation Museum in

Spencer. Craftsmen have been tackling rust and rot, which continued even while

the Texas was housed at Grant Park.

The public

can see the Texas and hear about the $500,000 restoration this weekend during a

“Civil War Weekend” at the museum.

The story of the Texas – its history, use and restoration – is fascinating.

The little engine that could

Built

by Danforth, Cooke and Company, the Texas was typical of locomotives of its

time. It weighed only 53,000 pounds and was wood-fueled. Its tender carried the

wood and a large water tank that fed the engine’s boilers. (The Texas in later

years operated on coal.)

The

Texas was a 4-4-0 American type, meaning

it had four lead wheels, four driving wheels and no trailing wheels.

Back

then, locomotives hardly were speed demons.

“The tracks

are right on top of the ground. There is not an extended elevated (section) that

would help you on a curve,” said McQuigg. At 20 miles

per hour and pulling 10 cars, the Texas was “doing pretty good.”

|

| The Texas when it was at Grant Park Cyclorama |

|

| (Max Sigler, preservation specialist, Steam Operations Corp.) |

McQuigg and

Scott Lindsay, whose company Steam Operations Corporation is handling the

restoration, say the development of locomotives over the years is a story of

technology.

“The country

grew,” said Lindsay. “We were very small with very primitive everything. As the

technology grew, everything got larger and heavier,” including locomotives and freight

and passenger cars.

The Texas and

other engines in the mid-19th century did not have air brakes.

“Stopping was more of an issue than starting.”

Lindsay

agrees the Texas’ ride was slow. But with this caveat: “When you compare to a

horse or buggy you were flying. You are going to another dimension.”

The hero of the Great Locomotive Chase

On April 12, 1862, the Texas took part in the famous Great Locomotive Chase, or Andrews Raid. Steaming in reverse, the locomotive pursued the fleeing General, which had been commandeered

by Union soldiers and civilians in disguise in what is now Kennesaw, Ga.

James Andrews and his raiders tried to destroy much

of the Western & Atlantic Railroad and communications as they rushed

northward toward Chattanooga. They achieved little success and eight of the

nearly two dozen captured participants were hanged in Atlanta as spies.

Andrews was among them.

|

| The Texas, with different number, in 1907 (Atlanta History Center) |

The

Texas continued its service after the war and was renamed the Cincinnati. It

was retired in 1907. Atlanta historian-artist Wilbur Kurtz saved it from

salvage, though he lamented its condition -- rust and rot left a shocking scene, he said. Money was raised over the next few years and the locomotive

eventually moved into its longtime Grant Park home in 1927.

McQuigg

said Kurtz, who restored both the Texas and the painting in the mid-1930s, did

what he could to stem the rust and rot present on the engine and tender.

'It's still the same vehicle'

Most people

probably don’t know that much of the locomotive is not original. The tender was

not with the Texas during the Civil War and the Great Locomotive Chase.

“A big

question for us is what is original and what isn’t,” say McQuigg, who has been

involved in railroad restoration work for about 25 years. “We want to know when

parts were added and subtracted.”

McQuigg says no matter the

changes – it’s the Texas.

|

| Tender (Max Sigler, preservation specialist, Steam Operations Corp.) |

“It is still

the same vehicle,” he said. “It went through the changes all locomotives would

go through in a 60-year service life.” He paraphrases something that his been expressed by the National Railway Museum in York, England: “A locomotive is

nothing more than a random collection of spare parts.”

The Texas’

wheels, boiler (the long tube), boiler jacket, pilot (cowcatcher), balloon stack

and parts of the frame have all been replaced over the years. At least some of

the wood of the cab on the engine is not original.

Lindsay says

that’s no surprise.

“Back in the

day, they were tools in the shed. They were not revered. They were constantly

changed. Every day they operated there was a chance something was broken or

worn out.”

The

locomotive also underwent changes when the gauge, the distance between rails,

was narrowed.

A lot of TLC in the back shop

|

| Example of pervasive rust (Max Sigler, Steam Operations Corp.) |

In North Carolina, Nathaniel Watts and

Max Sigler of

Steam Operations Corporation have spent months on the project, with much of the

work on the tender.

Rotten wood on the frame is

being replaced. The frame and wheel sets were disassembled and a few new pieces

fashioned, said Lindsay. The rusted bottom of the tender tank is being

replaced.

A contractor has used soda –

rather than sand -- blasting on the locomotive and tender.

“Sand is very

abrasive, and will clean metal to a shiny new surface,” said Lindsay. “It is

very abrasive and destructive. We don’t want something in marginal condition

and destroy it.”

The

restoration crew is aware the Texas is on the National Register of Historic

Places.

|

| Tender work (Max Sigler, Steam Operations Corp.) |

|

| More rust (Max Sigler, Steam Operations Corp.) |

McQuigg has

said he the AHC doesn’t want a “heavy-handed” restoration. He told the Picket

the last thing he wants is to see parts taken to the junkyard because officials

wanted to be true to the engine’s appearance in a certain era. Anything built

or put on from 1857 to 1907 will remain.

As for the

locomotive it, too, has suffered from rust, particularly under the boiler

jacket and a spot in the cab. The ash pan and ash pan door were rusted away. Some

parts of the engine need replacement.

Close analysis of paint scheme

When talking

about the Texas, you have to refer to certain points in its life – Its first

years as a wood-burning locomotive to its transition to a coal-burning machine.

And the century since it was saved and refurbished.

The Atlanta

History Center has been looking at various paint schemes the Texas has had during all those transitions. It

has not made a final decision on colors it will choose for the locomotive and

tender.

|

| Rear view of the boiler (Max Sigler, Steam Operations Corp.) |

For Lindsay,

no two train restoration projects are the same. But given its history, the Texas,

he said, is much more than just an old locomotive.

“It is a real

honor and privilege to work on something with great connections to a major

event of the Civil War. We are doing our best to make … (sure) it represents

the history of the United States.”

Lindsay says

it is unusual that both the Texas and General, which is housed at the Southern

Museum of Civil War and Locomotive History in Kennesaw, are still around.

“That is a

remarkable story in our throwaway society.”

COMING SOON: Decision ahead on Texas

paint scheme

Thursday, August 25, 2016

Where thousands of Civil War soldiers rest, there's a corner 'for ever England'

|

| Headstone replacement continues at Poplar Grove (NPS photos) |

Resting among the 6,100

Union soldiers buried at Poplar Grove National Cemetery in Virginia are 50

service members who served during other wars or eras. Not all are American.

British Sgt. Maj.

George M. Symons enlisted in the Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) in

1908, saw action early in World War I and was sent to Camp Lee in Petersburg,

Va., to help train American soldiers preparing for the war. Less than two

months later, on Oct. 8, 1918, he died during the influenza pandemic and was

buried at Poplar Grove. Symons left no wife or children.

On Saturday, the

cemetery, which is in the middle of a major rehabilitation project, will

sponsor a Symons grave rededication. A niece living in Michigan (along with her daughter and grandson), a British liaison and an

historian from what is now the U.S. Army’s Fort Lee will be among those

attending the closed event. A new marker has corrected information about the UK

soldier.

“He did not have

family,” said Betsy Dinger, a park ranger at Petersburg National Battlefield,

which manages the cemetery. “He does kind of have a family in the rest of us.”

With the exception of

special events and public tours, such as one scheduled for this Saturday

morning, Poplar Grove has been closed since November 2015. The biggest project

has been the replacement of all headstones, which since the 1930s had been flat

on the ground.

Nearly 4,000 upright

headstones have been put in thus far, said Dinger.

|

| Lodge walls now are violet, as they were back in 1872 (NPS) |

The cemetery’s lodge

is undergoing a major restoration, brick walls and other features are being

repaired and sealed and the park is addressing drainage issues across the

nine-acre site. Officials hope work is wrapped up this December.

“They are still

working on the pointing on the brick wall,” said Dinger. “The new flagpole

footing is coming along, as are the bases for the cannon which will be in the

area around the flagpole.”

Poplar Grove holds the

remains of several Native Americans who fought during the Civil War with

Federal units, among them the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters. Members of

the Menominee and the Stockbring-Munsee tribes made a visit several weeks ago.

“It was a real

privilege to walk around with them and learn about their culture,” said Dinger.

“I was especially moved at the prayers. You may not know a language but

your heart understands the words.”

|

| Boundary walls are being repaired and pointed. (NPS) |

Dinger has been busy preparing

for Saturday’s grave rededication. She speaks fondly about Symons. “My nephew

says when he comes (to visit) we have to see Uncle George.”

Dinger said a speech

from a British colonel and the Fort Lee historian will reflect professional camaraderie.

She expects two members of the Great War Association to wear British uniforms. “Last

Post,” a UK bugle call akin to “Taps,” will be played.

Because Britain did

not begin repatriation of service member remains until after World War I,

Symons has stayed in Virginia.

The park ranger made

reference to a stanza in “The Soldier,” written by English poet Rupert Brooke.

“If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is for ever England.”

That is for ever England.”

Saturday tour:

The third "Hard Hat tour" of Poplar Grove is set for 10 a.m.-noon

this Saturday. Reservations are necessary; contact park ranger Betsy Dinger at

(804) 732-3531 ext. 208.

Saturday, August 20, 2016

What new Camp Lawton dig director wants to learn about Union POWs, Rebel guards

|

| Ryan McNutt |

Ryan McNutt found

that when one door closes, a really cool one opens.

The conflict

archaeologist’s teaching contract at the University of Glasgow was coming to an

end late last year. McNutt had earned his master’s degree and doctorate at the UK

university and while in Europe had done research on the locations of

battlefields from the Middle Ages. Through the school's Centre for Battlefield Archaeology, McNutt had helped excavate a World War I site

(Somme in France) and others from World War II (Stalag Luft III in Poland and aircraft

crash sites in Scotland).

McNutt, 33,

ran across a job posting back in the States. Georgia Southern University in

Statesboro was looking for an assistant professor of anthropology. Duties

include overseeing the school’s Camp Lawton project.

“Lawton was

the main thing that attracted me to the job,” said McNutt, who will oversee GSU

research and archaeological excavations at the Confederate prison site a few

miles north of Millen.

The camp

broke into the news in 2010 when federal, state and campus officials announced

that its location had been confirmed and it was already yielding a trove of

artifacts.

But there’s been

no activity on the site in more than a year. McNutt’s predecessor, Lance Greene, took a position at Wright

State University in Dayton, Ohio, after the summer 2015 field school.

|

| Excavation at Camp Lawton (Courtesy of Hubert Gibson) |

For McNutt,

who worked on projects in the U.S. Southeast before going abroad, serving as the

Lawton director is an opportunity to continue Greene’s work and explore some of

his own questions about the prison, which was open for only six weeks in fall

1864.

“Preservation

is so bad on U.S. Civil War prison sites, especially Confederate ones,” said the

Alabama native. But not at Camp Lawton. Archaeologists have been helped by the

remote location of the stockade and relatively minor disturbances of the soil.

McNutt told

the Picket about some of his objectives:

-- Prisoner

of war camps are “excellent places to hide contraband, personal items you are

not supposed to have. If you are rousted in camp, left on a train early in the

morning, as they were (at Lawton) those are the kinds of things that are to be

left behind.” McNutt wants to know whether some of the shelter areas include

digging tools, stashes of forbidden resources or items used in trade with

guards. “That leads back to what are these guys doing to cope with aspects of

confinement and how are they resisting. How are they mentally resisting the

fact they are stuck here in this camp.” Contraband, McNutt said, can be “a

relatively powerful victory.”

-- He wants

to document how the 10,000 Union soldiers divided themselves up. The

men were to be grouped by regiments and companies. “That is the official

standpoint of Confederacy.” But there are good indications that at nearby Andersonville

(Camp Sumter), there was internal sorting by ethnicity. European coins or

tokens have been found at Camp Lawton and it is known there were many prisoners

of Irish descent.

|

| Friendship ring found at Lawton (Courtesy of Georgia Southern U.) |

-- McNutt

wants to learn more about how prisoners used the space available to them. It

was a cold, wet autumn and hundreds died. Getting the perspective from the fort

(Confederate) side of the camp will allow students to ascertain places that

could not be seen by guards.

Over three

years, Greene and his students worked on confirming the location of the

stockade walls and spent a lot of time in the prisoner area, uncovering a

communal brick oven and a dwelling hut. They excavated what is believed to be a

Confederate officers’ barracks, but were not able to identify other Rebel

portions of the site, including where the enlisted men lived.

Greene told

the Picket last summer that a big focus of the Camp Lawton project is

understanding the difference in the quality of life and the relationship

between prisoners and guards. McNutt concurs.

“There is no glass or ceramics in the prison area. They are

having to do with tin cups,” Greene said. “The Confederacy is giving them

nothing and they are getting bad cuts of meat if they get anything at all. A

tin cup was used for water and to eat soup. They have nothing else. They reused

items, railroad piece and metal scrap.”

McNutt said

he, too, will concentrate on the precise locations of Federal and Confederate

structures, including the stockade. He wants to find and excavate potential

corners.

|

| Brass keg tap (Courtesy of Georgia Southern U.) |

The presumed Confederate

barracks “is in the gray area.” Artifacts fit the time period. “They are of a

high-quality enough goods they were likely from the kind of stuff the officers

would have had around them.” Accounts by Union prisoner Robert Knox Sneden

indicate that the area should have been surrounded by kitchens, cookhouses and

cabins.

McNutt said

conflict or battle archaeology can be tough. The 1745 Battle of Prestonpans in

Scotland was over in hours. But such locations, where activity occurred in a single

day or over a few weeks, can provide exciting research opportunities, he said.

“It is such a

short burst of activity; they are almost perfect time capsules. You get these

really nice frozen moments in time. The occupation is so short you can tie this

down to specific weeks. Sometimes to specific regiments. I think there is a lot

of that at Camp Lawton.”

So a

relatively short time capsule may demonstrate how the prisoners coped with food

shortages, boredom and loneliness.

McNutt

expects to meet next month with Georgia and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service archaeologists

about objectives and research designs for the next phase of archaeology. (A

portion of the prison is in Magnolia Springs State Park and the remainder is on

the fenced site of an old federal fish hatchery.)

|

| Barracks excavation a couple of years ago (Courtesy of Georgia Southern U.) |

The Camp

Lawton director would like to see the earth turned again sometime in 2017 and a

campaign launched to renew public interest. “When exactly that starts is kind of up in

the air.”

McNutt has written what he loves about archaeology: “Researching the

past, thinking about the way people interact with each other, how we use

objects, and objects use us. How we create the present from the past, and craft

national and group identities from these created pasts. And how as

archaeologists, we can pick these themes apart.”

He’s

conscious of Camp Lawton’s ties to other prison sites in Georgia, including

Blackshear and Thomasville. Lawton was evacuated during Sherman’s March to the

Sea and prisoners were sent elsewhere. “I see all three of those sites

interlinked. They are all part of the same story. Camp Lawton can inform on

them and Thomasville and Blackshear can inform back to Camp Lawton.”

McNutt also wants

to restore public days at Magnolia Springs. Visitors can help in the

archaeology on certain weekends and visit a Camp Lawton museum just yards away.

“I believe

archaeology … should exist for education of my students and education of the

public at large,” he said.

Monday, August 15, 2016

Exhibit's 'Toy Soldier' is a photographic 'delusion' of haunting Civil War portrait of Edwin Jemison

|

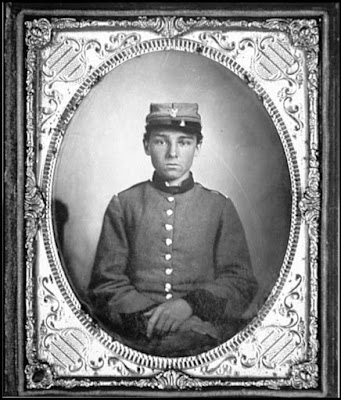

| Pvt. Edwin Jemison (Library of Congress) |

Wait a minute – I recognize him.

I was

scrolling through my personal Facebook feed recently and came across a post

with the image of a young Confederate soldier.

You no doubt

have seen the haunting face of Pvt. Edwin F. Jemison, a native Georgian who

enlisted at 16 and died at 17 at the Battle of Malvern Hill in Virginia while

serving with the 2nd Louisiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

The Facebook

image I saw was of a 2003 artistic interpretation of Jemision entitled “Toy

Soldier.” It was created by Brazilian artist Vik Muniz, who uses what is called

a playful and inventive approach in creating “photographic delusions.”

The text next

to the work reads: “Struck by the profound sadness in a portrait of a child

soldier during the Civil War, Muniz decided to re-create the portrait out of

plastic soldiers.”

Last week, I

paid a visit to the Muniz exhibit at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. I gazed

at his interpretation of iconic images of pop culture: Mona Lisa in peanut

butter and jelly, Che Guevara in black beans and Dracula in caviar.

But I spent

most of my time studying “Toy Soldier” from a variety of perspectives. It is

part of a triptych, or three panels.

The High

explained Muniz’ concept: “He assembled a distorted version of the image on the

floor and photographed it from an angle to correct the perspective. As a

result, some toy soldiers appear vastly larger than others, though they were

all the same size. The final work is presented as a triptych with depictions of

a horse and an American Indian, recalling subjects common to toy figurines.”

I’ve been

wrestling with the artist’s intent here, but perhaps the use of toy soldiers is

an example of innocence lost – and regained.

The American Battlefield Trust has a video featuring a National Park Service ranger at the Malvern Hill

battlefield. She details the brief service of Jemison, who enlisted within a

month of Fort Sumter’s fall and served in the Peninsula Campaign in Virginia.

He was decapitated by Union artillery fire during a Rebel advance on July 1, 1862.

Jemison’s

youthful face has graced magazine covers, books and other mediums, making him

the “poster boy” of wartime innocence loss.

While there

is a monument in Milledgeville, Ga., many believe his remains are among

the unknown at Malvern Hill.

Muniz, the

artist, is known for his interpretation of pop culture and celebrity. And it

was fascinating to see what he creates out of a variety of objects.

“From a

distance, the subject of each resulting photograph is discernible; up close,

the work reveals a complex and surprising matrix through which it was

assembled. That revelatory moment when one thing transforms into another is of

deep interest to the artist.”

The Vik Muniz photography exhibit at the High Museum of

Art runs through Aug. 21. Details here

Tuesday, August 9, 2016

For CSS Georgia conservator, artifact scoops in river meant having to make choices

|

| Archaeologists wash off railroad iron used as armor (USACE photo) |

Each time a

scoop of CSS Georgia artifacts landed last year on the deck of a barge in the

Savannah River, Jim Jobling made a decision.

A “CRL”

finding meant the item was going to Texas A&M University’s

Conservation Research Laboratory for long-term conservation. Landing in the “R”

pile meant that artifact from the Confederate ironclad was destined for river

reburial.

“Anything

that was unique and could add to our database of knowledge we kept,” said

Jobling, the lead conservator during the removal of the wreck under the

auspices of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “Nothing unique was thrown away.”

|

| Grapple used during mechanized recovery (USACE) |

Jobling spoke

of time constraints and salvage archaeology at a recent symposium at

the National Civil War Naval Museum in Columbus, Ga.

During the mechanized recovery phase of the CSS Georgia, two dozen archaeologists -- equipped in boots and safety helmets and using hoses

and rakes -- sifted through muddy piles of metal and wood brought up by a

five-finger grapple and a clamshell scoop.

The daily yield was

incredible: Pieces of casemate, an 1841 percussion pistol (below), telescope tube, shoes,

buttons, champagne bottles, bayonet handles and hundreds of other items,

including a massive 9-inch Dahlgren, somewhat of a surprise find.

|

| (USACE photo) |

Michael

Jordan, who is making a documentary about the project for the Corps, told the

audience that “scooping at the end is where the honey pot is.”

He described

Jobling, who works for Texas A&M, as master of a “ballet of artifacts

moving around.”

Jobling used PowerPoint

slides at the symposium to summarize a typical lift. In this case it was G54 -- a load brought

up by the grapple in mid-September 2015.

The CRL pile

in that lift included an anvil, a gear piece, chain, caulking hammers and wood

from a bucket. The R pile

included broken fasteners and twisted pieces built below the CSS Georgia’s

railroad armor. “Bent wood won’t tell me anything,” said Jobling.

|

| Items that were kept (top), items that were reburied |

Archaeologists

and conservators made a photographic record for each of 2,200 scoops and lifts.

The

mechanized recovery followed large-artifact recovery, during which Navy divers

brought up ordnance, guns, casemate and a propeller. For the mechanized phase, the barge crew and

scientists had images that showed them exactly where to scoop or scour the

river bottom about 40 feet below.

“There were

always surprises,” Jobling said in a recent phone interview. “In a zero

visibility environment, you don’t have a grasp on everything.”

In an ideal

world, archaeologists want to keep all artifacts, he said. But with limited

funding and time for the CSS Georgia recovery (it is being moved so that the

vital shipping channel in Savannah can be deepened), choices had to be made.

(Interestingly,

many items were pieces of Native American earthenware that may have drifted

down the river and settled in the wreck site).

While 140

tons of material was shipped, nearly that much was reburied in the Savannah

River.

Jobling and

the others worked six days a week and long hours during the mechanized

recovery. “Every day, something new was found,” he said.

“We were filthy at the end of the day.”

Wednesday, August 3, 2016

Three famous vessels: Conservation scorecard and biggest remaining mysteries

|

| H.L. Hunley as exterior is cleaned (Friends of the Hunley) |

Just for fun,

I asked three Civil War shipwreck conservators and a historian at last weekend’s

symposium in Columbus, Ga., for a scorecard on where the work stands and the

biggest questions they hope research will reveal. Here are the

responses, as provided at the “Wrecks, Recovery & Conservation” program at

the National Civil War Naval Museum. The scale is 1-10, with 10 indicating

completion:

Jim Jobling, CSS Georgia

Wreck raised: 2015 (another casemate section recovery scheduled for 2017)

Conservation: 1-2

Interpretation: 1

Biggest questions? We are an artifact dump site. I want to know how the CSS Georgia was designed and built. I don’t think we can answer that. We have the top and none of the bottom. There is no hull or engine. We have a challenge.

Wreck raised: 2015 (another casemate section recovery scheduled for 2017)

Conservation: 1-2

Interpretation: 1

Biggest questions? We are an artifact dump site. I want to know how the CSS Georgia was designed and built. I don’t think we can answer that. We have the top and none of the bottom. There is no hull or engine. We have a challenge.

|

| Michael Jordan |

Michael Jordan, CSS Georgia

documentary producer

Biggest questions? I want to know more about the crew’s lives. We are looking for a sailor’s diary. There are stories to be told. Also, more about the Savannah women who raised the money to build it.

Biggest questions? I want to know more about the crew’s lives. We are looking for a sailor’s diary. There are stories to be told. Also, more about the Savannah women who raised the money to build it.

Will Hoffman, USS Monitor

Wreck raised: Anchor in 1983, propeller in 1998, steam engine and section of hull in 2001, turret in 2002

Conservation: 5-6 (completion by 2035)

Interpretation: 8-9

Biggest questions? Why the Monitor sank while being towed to Beaufort, N.C. It may have been failure of the hull, which had a riveted V shape. It belly flopped in the waves. Also, who were the two sailors found in the turret and how should we present the artifacts (at the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Va.)?

Wreck raised: Anchor in 1983, propeller in 1998, steam engine and section of hull in 2001, turret in 2002

Conservation: 5-6 (completion by 2035)

Interpretation: 8-9

Biggest questions? Why the Monitor sank while being towed to Beaufort, N.C. It may have been failure of the hull, which had a riveted V shape. It belly flopped in the waves. Also, who were the two sailors found in the turret and how should we present the artifacts (at the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Va.)?

Wreck raised: 2000

Conservation: 7 (About five more years)

Interpretation: 8-9

Biggest questions? What caused it to sink. We are going back to the materials; there were flaws in the metal. What was happening may not be one thing. I am confident we can pin it down. We want to solve the case.

Conservation: 7 (About five more years)

Interpretation: 8-9

Biggest questions? What caused it to sink. We are going back to the materials; there were flaws in the metal. What was happening may not be one thing. I am confident we can pin it down. We want to solve the case.

Monday, August 1, 2016

CSS Georgia, H.L. Hunley and USS Monitor conservators detail challenges, rewards

|

| Will Hoffman details USS Monitor's remarkable engine |

One was

reduced to salvage items. Another was a traditional shipwreck. And the third

came up largely in one piece, its contents a time capsule of innovative naval

warfare.

The discovery

and recovery of Civil War wrecks are a blink of the eye compared to their

cleaning and the decades it takes to conserve items as large as a turret or as

small as matchstick.

The complexity,

cost and challenges of conservation was the subject of the “Wrecks, Recovery

& Conservation” symposium held Saturday (July 30) at the National Civil War Naval Museum in Columbus, Ga. The speakers featured preeminent conservation

experts who have been tasked with helping bring the stories of the CSS Georgia,

USS Monitor and the H.L. Hunley to the public.

“What is the

long-term process of bringing these articles to life to us?” Jeff Seymour, director of history and education at the Columbus museum, asked before the conservators spoke to 25 patrons who listened closely and viewed PowerPoint slides.

It starts with patience. Conservation can take decades.

CSS GEORGIA: Working with salvage

Seymour

called the Confederate ironclad scuttled in Savannah, Ga., “the hot recovery

topic right now.”

Filmmaker

Michael Jordan, who is producing a documentary, highlighted three aspects:

Ordinary people doing extraordinary things (22 Savannah women raised the

equivalent of $2.6 million to build the boat), failure sometimes being good

(while it was too underpowered to engage in battle, the CSS Georgia was a

strong deterrent as a floating battery), and being forgotten is the best way to

being saved.

Jim Jobling (above),

chief conservator on the CSS Georgia, provided details of the unique condition

of the boat, which is being moved as part of a channel deepening project at the

busy port. It was salvaged a couple times after the war. Buoys and dredges caused

damage in the decades since and a swift current makes recovery difficult.

“We are not

dealing with a wreck,” he told the audience. “What we have is a salvage dump

site.”

While the

Savannah River is only 42 feet deep, visibility for divers often is negligible.

An array of technology and voice commands led Navy and U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers contract divers to artifacts.

“This is

archaeology by Braille, but we have a positioning system,” said Jobling. The

location of items is recorded and the divers work in 10-foot squares. (A large

portion of the CSS Georgia was brought up in 2015, but crews are returning in

2017 to bring up the east casemate. Numerous attempts were made to bring it up,

but there was not enough support beneath the artifact. Iron beams will be used.)

|

| Several of these were found in the wreckage |

Another

challenge was building trust and sharing skills with the U.S. Navy salvage team

that brought up larger items, include a propeller and several guns. (That group

also provided brute strength: One Navy diver carried two Brooke gun bolts

totaling 180 pounds to a basket.). “Once they learned the history, they became

part of it,” Jobling said.

Before he

traveled from the conservation lab at Texas A&M University, Jobling believed

the recovery would yield 35 tons of material. Jobling shipped 140 tons (15,500

artifacts) in numerous two-day shipments.

Twenty-four

tanks are involved in the process, and hundreds of artifacts currently are

being rinsed to remove chlorides. “We have only started the conservation

process,” which could last 10 years.

USS MONITOR -- Understanding your artifacts

Chief

conservator Will Hoffman, who works at the USS Monitor Center at the Mariners’

Museum in Newport News, Va., spent a good amount of his talk describing the

science and techniques of conservation once items are in the lab.

|

| Will Hoffman |

He described forces

that cause corrosion and technology that can combat further damage.

Iron can

become very brittle after years of exposure to ocean chlorides. Hoffman said it

very important to know the materials they are working with before attempting to

take items apart for further cleaning. “You only get one shot at it.”

When building

a conservation plan, Hoffman said, it is important to know three things about

an artifact: How was it made? How was it used? How has it degraded?

Experts often

work first on smaller pieces to refine techniques. Sometimes it can take months

to build a rig that can eliminate concretion (hardened layers of sand and

shell) fixed on an item, he said. “I have to do this step to do this step

before I take it apart.”

The work,

which follows a protocol, is painstaking. For example, 10 tons of concretion

were removed from the Monitor’s remarkable engine.

|

| View of the engine (Courtesy: The Mariners' Museum and Park) |

|

| Reverse osmosis tanks (Courtesy: The Mariners' Museum and Park) |

Those working

on the CSS Georgia, by contrast, are stymied by the fact no blueprint or plans

are known to have survived.

Adding to the

complexity of the Monitor project was the recovery of the remains of two

sailors found in the signature revolving turret.

Despite

facial reconstructions and the study of their DNA, no formal identities have

been made. They were buried at Arlington National Cemetery in 2013. “It was a

beautiful ceremony,” Hoffman said.

Personal

items belonging to the pair are being held in case confirmed descendants step

forward.

H.L. HUNLEY: Coming to life

|

| Paul Mardikian with Jeff Seymour |

Senior

conservator Paul Mardikian, who previously did conservation work on the CSS

Alabama, lost off Cherbourg, France, provided an overview of that shipwreck and

the Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley.

The Hunley,

which was the first combat submarine to sink a ship, was lifted out of

Charleston Harbor in August 2000.

The conservation

team was among the first to use digital scanning. Ten tons of sediment from were

removed and the iron vessel has been through electrolysis and several chemical

solutions to help loosen the concretion.

Conservators,

because of the toxic environment, wear special masks and protective gear when

working during the day (the tank refills at night). Adding to worries was

spilled mercury from the boat’s depth gauge. Experts must be careful with the

pneumatic drills that chip away at concretion.

|

| Cleaning of exterior (Friends of the Hunley) |

They had to

take extreme care: The bodies of the eight crew members who died after the sinking

of the USS Housatonic were inside. “This is a grave, a battle site, a crime

scene,” Mardikian said. “You have tangible human remains.” X-rays could damage

remaining DNA.

“It is

relatively rare to find human remains,” said Mardikian. Among his duties,

beyond studying them, was to ensure the remains would not decay before their

2004 burial.

“Saltwater is

good for (preservation of) human remains, bad for (metal) corrosion, he said.

The scientists

had to create their own conservation plan and techniques for such a unique

scenario. And there were surprises: Among them, no gun was found inside, but a

matchstick was. “They are the most ephemeral objects to conserve,” Mardikian

said of an item likely used to light a smoker’s pipe or a lantern.

Remnants of

clothing fabric had the consistency of toilet paper. Cashmere and silk, he

said, are among the most durable. In the realm of you get what you pay for, the

artifacts made of the highest quality have proven to be the easiest to

conserve. The famous lantern, he said, was made of inexpensive tin.

Over the 16

years, there have been occasional setbacks: Erratic funding, delays and drainage

problems with the conservation tank. It’s a 10-20 year process, Mardikian said.

|

| A view of the July 30 symposium in Columbus, Ga. |

But there

have been huge rewards. Deconcretion of the submarine’s exterior and interior

have brought the warship to life. “When you look at the sub design, it is splendid.

It is like looking at the sub for the first time,” Mardikain said.

“The cast

iron is very beautiful. You want to kiss it. But it is very corroded.”

As he

continues to guide conservation work on the Hunley at Clemson University’s Warren Lasch Conservation Center in North

Charleston, S.C., Mardikian does other work with his company, Terra Mare

Conservation.

One project was working with a venture by Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos to

conserve a Saturn V rocket engine that propelled Apollo 11 to the moon in 1969.

Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin told Mardikian he was fortunate to work

on such an array of projects: The slow, hand-cranked Hunley and the most-powerful

liquid-fueled engine.

LATER THIS WEEK: Remaining mysteries

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)