|

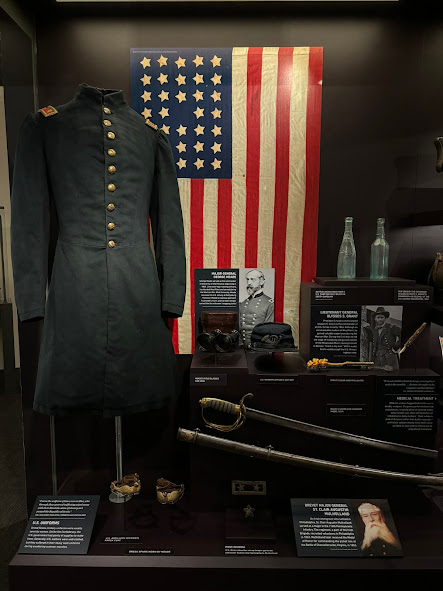

| Capt. Hawley's frock coat and kepi in a 2nd-floor exhibit at Monocacy (NPS photo) |

Capt. William

Hawley, Company E, 9th New York Heavy Artillery, was wounded in the

arm on July 9, 1864. His hat and frock coat have been on display at Monocacy National Battlefield near Frederick since 2007.

Tracy Evans, acting chief or resource education and visitor

services at the park, said Caring for Textiles of Washington, D.C., patched 10 small holes in the kepi's wool and reattached several open seams,

including the leather trim.

At Monocacy, outnumbered Federals delayed Confederates bent on taking Washington. Union artillery did a lot to slow the Confederate advance, despite the latter having more guns. Jubal Early did not use the majority of his ordnance because he believed only militia was in his way. (Hawley's unit served as infantry at Monocacy.)

By the time Rebel troops reached the capital’s outskirts, Union reinforcements had arrived.

Park officials say the revamped museum will tell more of the individual stories of soldiers and others. (Hawley's frock coat at left, NPS photo)

“The

currently fiber-optic battle map will become a much larger map in the center of

the museum that will be accessible,” Evans said in an email. “Surrounding

exhibits will talk about all the people who lived on the farms, and how their stories

intersect with the war and the Battle of Monocacy.

“It will also

explore information about the campaign, battle, soldiers, post-battlefield hospital,

(and) aftermath of the war/memorialization/effect of postwar on the people the

war ultimately freed,” the ranger said.

Park officials anticipate the visitor center museum will close for renovation in September and reopen prior to Thanksgiving.

Collector

Richard Abel, in a comment on the park’s Facebook post about the kepi, said the Hawley cap and the coat were purchased from the family via an antique store in

Gettysburg, Pa.

“I was always proud of this gift, to return the uniform to

where it belongs, the field of battle, & to be viewed by the public,” he

said. Abel donated many items, which were first kept at Gambrill Mill when it

served as park headquarters.

Evans said Abel’s donations helped make up for a shortage

of artifacts at the time. She added officials do not know whether Hawley wore that specific kepi and coat at Monocacy, only that he had them during the war.

Hawley was in his early 40s when he enrolled in Auburn as a lieutenant in the 138th New York Infantry in August 1862. The unit was designated as the 9th New York Heavy Artillery a few months later.

|

| 9th New York Heavy Artillery at a Washington, D.C., fort (Library of Congress) |

The regiment helped defend Washington and participated in the Overland

Campaign in Virginia before it fought at Monocacy, both times fighting as infantry. It served until the war’s end, suffering 461 casualties, nearly half from combat.

Hawley, who led a company, was honorably discharged in September 1864. Some newspaper accounts

said his arm injury was slight, but it may have been more serious. He

apparently applied for a pension in 1880 and died at age 77 in Wolcott, N.Y., in 1897, according to findagrave.com.

Evans says Hawley’s coat, featuring red shoulder boards and artillery buttons, is in very good condition. “The conservator created some padding to add to the mannequin to ensure the shoulders did not sag.”

While he was a captain at Monocacy, Hawley's shoulder bars are those for a lieutenant.

The coat was "rested" from the effects of light in spring 2020. "In the new museum, the frock coats will be rotated so that they have some rest from the mannequins and light," Evans said.

At Monocacy, Union Maj.

Gen. Lew Wallace’s troops used his limited artillery and the terrain to their

advantage, says park ranger Matt Borders.

“Deployed

along the ridge south of the Monocacy River, these cannons had a wonderful

field of fire and high ground from which to engage. The scattered deployment of

the artillery also gave the impression of more cannons than there actually were

or the possibility that the ridge hid more cannons,” he says.

|

| Ranger Evans adds curatorial stuffing to arm of frock coat (NPS photo) |

“As

Confederate forces got south of the river, more of the Federal artillery was

shifted to the left of their line; eventually five of the six rifled artillery

pieces were deployed on the rising ground near Thomas Farm to engage

Confederate infantry and some of their artillery support,” Borders wrote in an email.

“It was the presence of these cannon that helped hold the Federal flank until 4 p.m., at which point they had used all their long-range ordnance and were compelled to retire. The Federal infantry stayed in line from 4ish to 5 p.m. in large part to make sure their artillery can successfully withdraw from the field."

All the while, Confederate artillery, which had been pushed forward into the very front yard of Best Farm, was firing across the Monocacy River enfilading the Federal line.

"Hawley and his men were some of the troops holding the line as the Federal artillery withdrew and were eating that enfilading fire coming from across the Monocacy River," said Borders.

This fire, along with an infantry attack against that same flank, eventually unhinged the Federal position, forcing it to give way around 5 p.m.“

.jpg)