\ |

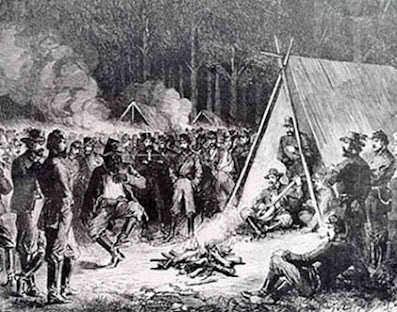

| Sam Sweeney (in tent), drawn by Frank Vizetelly for Illustrated London News |

Jine the cavalry! Jine the cavalry!

If you want to catch the Devil, if you want to have fun,

If you want to smell Hell, jine the cavalry!

We're the boys who went around McClellian,

Went around McClellian, went around McClellian!

We're the boys who went around McClellian,

Bully boys, hey! Bully boys, ho!

Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, ever the dashing figure, was known

to dress handsomely and tap his feet joyously. On the trail, or by the campfire after a hard day’s ride, the Confederate

cavalier enjoyed the rollicking and homesick songs played by his personal, “appropriated”

banjo player, Sam Sweeney. “Jine (Join) the Cavalry” was a standard among Confederate horsemen.

Sweeney, from Appomattox, Va., was one of the famous Sweeney

brothers, three Irish-American musicians who played at raucous minstrel shows and even for

Queen Victoria in the years before the Civil War.

|

| Sam Sweeney |

Older sibling Joel Sweeney, experts say, is the first

documented white man to play the banjo, having learned the music from slaves by the mid-1830s. Considered

by many to be the first pop star in America, the so-called “father of

the banjo” was considered an innovator in the use of the five-string banjo, an

instrument with roots in Africa.

“He was the one who brought (the banjo) into white, middle-American

culture,” says David Wooldridge, a

museum technician with Appomattox Court House National Historical Park.

Wooldridge recently gave a talk about Sam Sweeney at the

Museum of the Confederacy’s venue in Appomattox.

“His brother (Joel) cast a long shadow and for a long time …

got all the credit,” Wooldridge tells the Picket. “Sam was supposed to be just

as good as his brother, or better.”

Joel and Richard Sweeney died before the war. Sam

Sweeney, also an adept fiddle player, joined Company H, Second Virginia Cavalry,

in January 1862. His skills and fame quickly came to the attention of Stuart,

who insisted the banjo player join his headquarters.

Col. T.T. Munford, from whom Sweeney was “borrowed,” later wrote, “Stuart’s feet would

shuffle whenever he was in Sweeney’s presence, or even at the calling of his

name.”

“Lorena,” “Cottage by the Sea,” “Soldier’s Dream and “Old

Gray Mare,” were among Stuart’s favorites, and Sweeney was often accompanied by

a bones player and tambourine.

Sweeney rode with Stuart during several notable campaigns,

including Gettysburg.

"Sam Sweeney's personality was much the same as his fun loving general and . ... he followed the dashing cavalier playing and singing songs that he and his brothers performed for many thousands of people," wrote John R. Broughton in a J.E.B. Stuart Birthplace Preservation Trust newsletter. "Wherever Stuart went, Sweeney was not far behind, his banjo ready."

"Sam Sweeney's personality was much the same as his fun loving general and . ... he followed the dashing cavalier playing and singing songs that he and his brothers performed for many thousands of people," wrote John R. Broughton in a J.E.B. Stuart Birthplace Preservation Trust newsletter. "Wherever Stuart went, Sweeney was not far behind, his banjo ready."

The Charleston (S.C.) Mercury newspaper has this fascinating tidbit on Jan. 16, 1863:

"Are you readers aware that Gen. Jeb Stuart carries with him wherever he goes, in all his circuits and raids, a brother of Joe Sweeney, the famous banjo player? Such is the fact. Sweeney is also a banjoist, and Stuart calls him his band. He carries his banjo behind his saddle, wrapped up in a piece of oil cloth, and whenever the cavalry stops, even to water their horses, the band strikes up on the banjo and picks a merry air. The performance of the banjo band in Pennsylvania drove several Dutch farmers raving distracted, for Sweeney swore that his banjo strings were made out of the viscera of their departed relatives and friends!"

Two years into his military service, Sam Sweeney passed away at age 32 on Jan. 13, 1864, in winter camp. He likely never fired a shot in battle.

A grieving Stuart wrote of the loss to his wife, Flora. ”I Suppose you heard the sad tidings of poor Sweeney’s death. He died of small-pox while I was gone. His loss is deeply felt."

The general would himself be dead four months later, fatally wounded at Yellow Tavern, Va.

The general would himself be dead four months later, fatally wounded at Yellow Tavern, Va.

It was not until June 2010 that a headstone went up in Orange County, Va., to remember Sam Sweeney.

Wooldridge, a banjo player, helped organize a May 2013 event at Appomattox honoring the legacy of the musical family.

|

| Flyer for 2013 event in Virginia. |

Among the performers was Sule Greg Wilson, a musician, folklorist and writer living in San Diego.

Wilson considers the Sweeneys to be early crossover artists, the first to appropriate African-rooted music to play before white audiences in America.

"I would say (the banjo) became a more harmonic instrument. The European sense of rhythm and melody is a different aesthetic than the African one."

Among the songs played at the gathering was "Grapevine Twist," an 1840 selection attributed to Joel Sweeney. But Wilson doubts Sweeney actually created the tune.

Although some songs of the era were about love, Joel Sweeney would play selections that appealed to everyday folks.

|

| Sule Greg Wilson at Appomattox (courtesy of artist) |

The Sweeneys would often perform in blackface during minstrel shows, a colorful if now-controversial form of entertainment that featured comedic skits and music that often would parody African-Americans and other ethnic groups.

Rhiannon Giddens, a member of the African-American string band the Carolina Chocolate Drops, said of minstrel music. “It is not hard to love it because the music is awesome. The words they are problematic. … There are some horrible words.” The earlier minstrel acts were not as racist as those once slaves were freed. Still, she said, the music tells us what was going on in America at the time and is part of our history.

A teaching lesson plan produced by the park says the story of the Sweeneys is part of the rich cultural patchwork of the United States.

“For, within the story of the banjo in America is the story of American culture; a story of cultural diffusion, a story of the power of music to bring disparate sections of our society together to create something distinctly American.”

• Videos: Wilson plays at Appomattox on “Sanford Jig” and another selection.

PART TWO: Banjo’s African roots, minstrels show and the instrument’s popularity during the Civil War. Click here for post

"The music tells us what was going on in America at the time and is part of our history." I love this attitude. Most times people want to efface the historical record if it is offensive or politically incorrect. To me it is dishonest, and smack of historical revisionism. I have been impressed that the Chocolate Drops have embraced this part of their heritage, rather than turn away from it. It is such a rich heritage. The WPA slave narratives are a fascinating read. This is something I have always wondered about: how did a traditional African musical instrument become so synonymous with white southern stereotypes? I think this comment might be on to something: "I would say (the banjo) became a more harmonic instrument. The European sense of rhythm and melody is a different aesthetic than the African one." I look forward to the next post. Additionally, I am sure the movie "Deliverance" affected people's perception of the banjo as well.

ReplyDelete